There are two notable things about Old Man's Beard. One is that it's one of the few times that Professor Yaffle actually gets the object right, as he correctly identifies that 'Old Man's Beard' is just the nickname of a climbing plant, and goes on to give five separate names for it. Yet also notable is how often during the episode Oliver Postgate's voice drops out of Bagpuss' and into his standard 'narrator' voice. Postgate does a fantastic job giving life to Bagpuss, Yaffle and some of the mice, and so a small lapse like this can be easily forgiven.

In keeping with the discussion on the objects of the series, then while Oliver Postgate expressed how difficult it was to think up new stories, there are around another season's worth of objects scattered throughout the programme. This episode features shots of a sewing wheel, a Kinetoscope and a bottle with feathers in it.

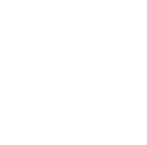

For more cod psychoanalysis of what are really just characters for pre-schoolers, how about The Elephant? Interest is stirred by Bagpuss' story of an elephant that gives up its ears for mice. Could this be Bagpuss's way of saying he feels emasculated by the mice, that he gives some of his own energy up so that they might wake? Probably not. In fact, what's more curious is the story of a pink elephant, which is well-known as a euphemism for alcoholism.

In an earlier version of the Bagpuss & Co microsite, I gave ratings out of five for each episode. The Hamish got just one, which seems very harsh, and this particular episode was the fourth highest-rated with a mark of four. Quite how I came to this conclusion is now beyond me, as this is a very bog standard edition of the programme, heavy on both song and illustrated stories, containing little of the interaction between regular characters that give episodes their full charm. That said, Gabriel and Bagpuss attempting to sing, out of key, is a funny moment to end on.

Look again at The Fiddle. In many ways what seems like an unremarkable episode of Bagpuss is actually the most innovative of all. For the only time one of Bagpuss' "stories" is actually illustrated by "real-life" footage. Instead of a cartoon, we discover that Bagpuss at some time travelled to the West of Ireland and met a leprechaun. This is all demonstrated by use of the actual puppet, rather than a series of still paintings. Even more unique, this becomes a story-within-a-story as the leprechaun asks Bagpuss to think of another tale. Bagpuss being able to tell stories by 'thinking' them was a recurring feature of the show, but this extra element elevates the series to Bagpuss by way of Inception. And where was Emily while her beloved Bagpuss was abroad on his holidays?

But the most fascinating segment of all is the single example of post-modernism in the series. When Yaffle scoffs that leprechauns aren't real, Gabriel, always one to contradict, states "Well, perhaps we aren't real, either." It's not only an interesting commentary on the show itself, but also suggests that Gabriel (a religious name, note) is aware of his tenuous existence, brought to life by Emily's will. Sadly, there's no real payoff in the series, and this line of thought goes nowhere... this isn't, after all, a slow-burning, plotline-heavy show like The Wire. But, in its favour, Bagpuss is so good that it's one of the few programmes out there that wouldn't be improved by having Omar in it.

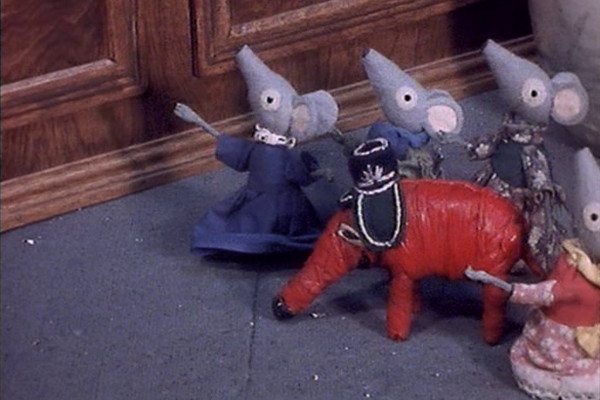

Although Bagpuss is a slow-paced, deliberately old-fashioned children's programme that can be watched by all ages, it's not without occasional moments that could trouble your inner Mary Whitehouse. The Owls of Athens contains a cheeky song where a banjo medley replaces rhyming words, some of which are slightly rude – such as Madeleine stopping herself from saying "bum". This particular episode has Bagpuss, almost inexplicably today, telling the story of how he met a topless mermaid in a bar who "sat on my lap". The mermaid, as illustrated, is clearly only in the first stages of puberty, making me feel extremely uncomfortable as I took the screen cap.

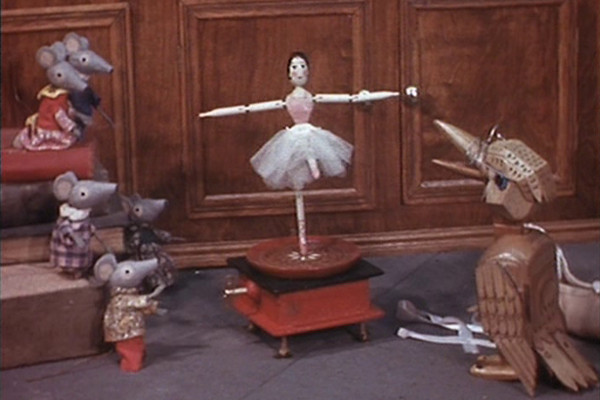

Although such things are produced out of innocence from a bygone age, tabloid headlines alert us to so much of 1970s BBC programming being tainted. Gabriel the Toad was actually first used by Peter Firmin in the 1960s programme Musical Box... a programme that had Rolf Harris as one of its hosts(!) There is probably more movement from Gabriel in this episode than any other, and, while on occasion he's the result of stop motion animation like the other characters, he was the only one that could be used as a puppet. There's a discord there, with mixed signals being sent to the brain... the rest of the characters move in slow, disjointed, stop-and-start stop motions, when suddenly through this haze a character begins to move rapidly in real time, speaking with a masculine voice in strict counterpoint to the fey tones of the others. Basically, it's unnerving. Yet despite such reservations, this is the first episode, and as a result feels that bit more special.

Bagpuss was never a "message" series, and while it's fun to imagine that there's a class war between Yaffle and the mice (Yaffle was based on a mixture of Oliver Postgate's stuffy uncle and Bertrand Russell), it's really just a light show for kids. However, in his autobiography, Postgate admits that the union activities of the early 1970s troubled him deeply, and this does manifest itself here in this episode with the mice refusing to work unless they're allowed to sing. "Mice not sing – mice not work. Mice... strike." However, he would save serious political commentary for his second most famous creation, The Clangers, with the October 1974 short Vote for Froglet.

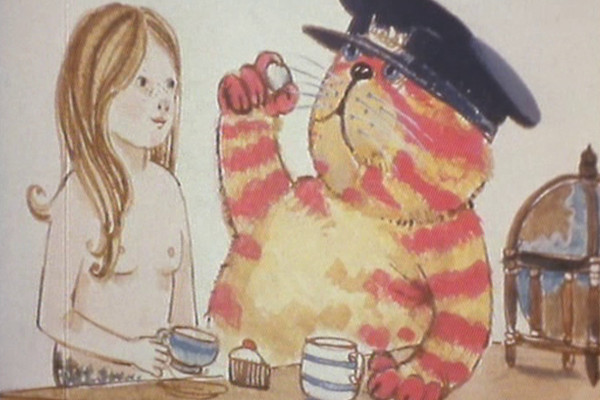

The Ballet Shoe concludes with perhaps the most charming and touching moment in all of Bagpuss – Professor Yaffle, never one to let his feelings show, is moved by a musical ballerina, and finds himself dancing with her.

Traditionally the most popular episode of Bagpuss, whereby the Mice play a trick on Yaffle, trying to convince him that they've created a biscuit-making device. It's good, if a little singular in intent, and ends with the various characters being aware of their symbiotic existence with Bagpuss. Knowing that when Bagpuss falls asleep, they too become lifeless, they rush to place the mill back in the window and assume their places before an exhausted Bagpuss loses consciousness.

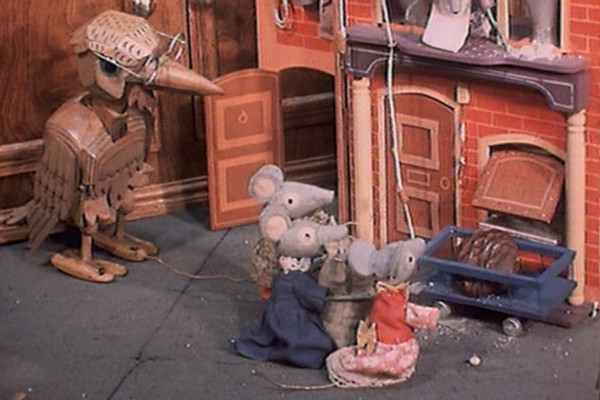

Perhaps what's truly extraordinary about this series is how much genuine life the characters seem to have. A mixture of woods and cloths, all animated in a charmingly primitive way, they nevertheless manage to come alive. Witness an amusing moment around the 11 minute mark, where Janie Mouse, pushing a trolley, turns to give Yaffle an accusationary stare before returning to the rear of the "mill". The mice are simple, basic creations, without even the luxury of movement in their eyes, and yet these small moments of interplay bring their spirit to the fore.

The most psychologically intriguing episode of Bagpuss, as Professor Yaffle takes one of just two sole turns as storyteller (the other being in Flying) and crafts a tale of a wise old Chinaman that lived on an island with only turtles for friends. Part of the wise man's reason for liking the turtles is that "they didn't talk and ask him silly questions", while he smashes a bridge to isolate him from a nearby island. Without realising it, Yaffle is revealing his inner need for isolation and his inability to form relationships with those around him. Freudians that watch the show will also regard Yaffle as an anal retentive, with his constant need to describe the object of the week as "filthy" or "dirty".

Normally Gabriel saying "we know a song about it, don't we?" will sink an episode stone dead (and you wish that, just once, the mice would lie and say they've lost the roll of music for it), but even this element is strong here, with quite a pleasant calypso that doesn't outstay its welcome. There's more time for story in this instalment, too, as, while the episodes are generally timed to precision (every episode lasting between 14'31 and 14'34 minutes exactly), the introductions to the episodes vary in length. Generally it takes around three-and-a-half minutes from the opening of the episode to Yaffle climbing down off his bookshelf to see that week's object, an age in modern terms, and a sizeable chunk of each episode, but charming nevertheless. However, the final two episodes (Flying and Uncle Feedle) take over 4'45m, whereas The Wise Man is able to blast through it in less than three minutes. I've studied the episodes over, and can see no difference, so can only assume it's the speed of the introduction.