The Pertwee incarnation of the Doctor isn't one that's aged especially well, particularly in his first two seasons before the character was softened. A very patriarchal, overbearing rendition of the character, and perhaps never more so than here, where he basically spends the whole story bullying Jo.

However, whatever the modern reception to the third Doctor, it's very much the intrinsic character. It's even in the name: he's a Time Lord, a member of an elite. While the character can be likeable, anarchic... silly, even... he's an alien with a superiority complex, not your best friend without any flaws.

Christopher Eccleston - who made a flawed yet commendable attempt at reviving the role in 2005 - was on record as not liking the Doctor's middle class roots. In his 2019 autobiography I Love the Bones of You: My Father And The Making Of Me, some of Chris's comments on the character as he saw it included: "Doctor Who seemed to me like your typical white middle-class authority figure. He was an upper-crust eccentric, very male, posh. [...] The role - posh, received pronunciation - needed changing. And I changed it."

Such views about the Doctor's class status are perfectly valid, yet growing up working class, it never particularly occurred to me that the Doctor was any different - possibly because so many people on television were middle class with RP accents back then. But to change the core of the character is to remove its fundamental underpinning. It's not a question of what's possible within the show's made-up SF background, it's a question of how far can you remove it before the character stops being "The Doctor"?

It's not about the physical reality of whether the Doctor could change into a body with different class or gender, within the fiction and the reality of making the show, it's about continuation of the subtextual themes underpinning said character. It's why, for example, the Doctor could never really regenerate into a female - sorry, Jodie fans. Such things aren't about misogyny, restricting opportunities or "glass ceilings", it's about the fundamental basis of character. So yes, the third Doctor is a bit of an idiot at times. That's what the Doctor is.

Away from such musings, The Dæmons ranks highly here, and even I'm surprised. The plot resolution is one of the all-time stinkers, the third Doctor is at his most unlikeable, and yet... is has something. Maybe it's the characters, the pacing, or the fact that so much of the location filming is on multi-camera, giving it the same feel as regular studio scenes?

On the extremely unlikely climax, Terrance Dicks said in the "making of" featurette The Devil Rides Out that: "I was never totally happy with the ending of the Daemons, ummm, simply because I, I'm, I'm very keen on logic, you know, and umm, it seemed to me, that umm, the Daemons, if they'd been observing Earth, would have seen many more instances of unselfishness and self-sacrifice. So when Jo's offer throws him into a total tizzy, you know, I mean, I never quite bought that. I never quite believed it."

A strong story with high production values, a very strong guest cast and a superb set of scripts for Roger Delgado as the returning Master. Sadly it doesn't quite maintain its brilliance over all six episodes, being a very good story, but just falls short of being a great one; there's a little too much padding in the middle, and a feeling that the regulars are beginning to enjoy themselves a little too much. In particular, there are some moments where it's Jon Pertwee on screen rather than the Doctor, if only for a second.

It contains a great opening and closing, and some of the most developed supporting characters seen in the series. An interesting element of the commentary track features Terrance Dicks describing writer Malcolm Hulke as a "Top Class B", but not on the level of "Bob Holmes", or "even, in a sense, the Bristol Boys" (Baker and Martin). While Hulke not being regarded as highly as Robert Holmes isn't surprising, it's perhaps startling that Baker and Martin's budget-busting scripts would be regarded in higher standing by Dicks.

Also on the commentary is director Michael Briant claiming to have come up with the idea of the sonic screwdriver during Fury From The Deep. Working on the serial as an assistant director, they discovered that a door had been fitted the wrong way round, with no locking mechanism present, only the screws. In order to get out of this production tight spot, Briant states that he devised the idea of the Doctor having a device that could free him just by removing the screws.

The Pertwee era is perhaps one of the most mannered by time, and so as a viewer in the 21st century you need to meet it, rather than it meeting you. People will regularly be referred to as "My dear...", "Old chap..." or, as here, a woman is regarded as "quite a dolly".

With The Mind of Evil, this sense of the time it was made is perhaps even greater. The last hanging in Britain was in 1964, with the death penalty suspended in 1965 and eventually abolished in December 1969. Less than a year later, production would begin on this story, which would feature an alternative to the death penalty - wiping all destructive impulses from a prisoner's mind.

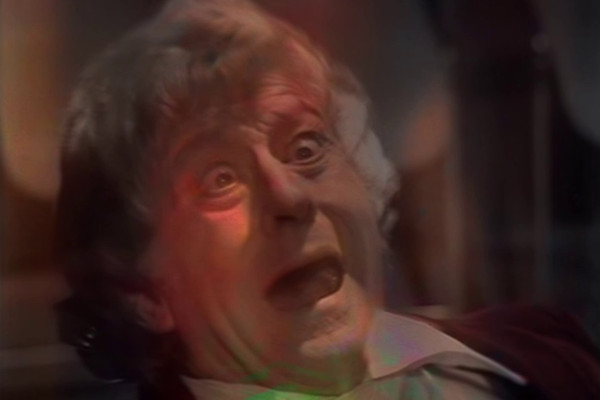

Jon Pertwee has a striking presence in the lead role, particularly in these earlier stories, though his acting does have a definite range. With his rubbery, expressive face, his attempts to show fear or the force of attack can sometimes look unintentionally comic, as in the screenshot above, the first page screenshot from Devious, or where he's being strangled by a telephone wire during Terror of the Autons. (Spearhead From Space, containing similar gurning, can at least be given a pass as it's arguably played for laughs on that occasion.)

The Mind of Evil isn't traditionally regarded as a top rank story, as it's a little too "busy" in terms of plot and relies perhaps too much on coincidence. But it's very much loved here, and is also Katy Manning's favourite tale. Released on VHS in black and white, it was restored to colour via chroma dot colour recovery for episodes 2-6, while the first episode was manually colorised. Although it's to the credit of the people who worked on bringing it back to full colour, it's not one of the most successful in this regard.

While we're in a wonderful time where all of the Pertwee stories are now completely in colour, the levels on this one, particularly the flesh tones, tend to ebb and fade consistently. Perhaps some years in the future the technology will be able to refine it even further, though it's still very watchable. This issue isn't, incidentally, part of the screenshot above - this shot involves the Doctor seeing nightmares of fire, inspired by Inferno.

A story of some brilliant wit and invention from Robert Holmes, who Terrance Dicks described as "infinitely the best writer" to have worked on the programme. With the Doctor and Jo accidentally caught in a miniaturised form inside an electronic zoo, they must piece together the elements of the story and ensure their escape.

It's innovative and creative, albeit "light". There are some areas where it could be even better. Holmes deliberately writes the inhabitants of a 1926 ocean liner as broad archetypes, but it would have been fun if they'd been written as real people. The other way it could have been improved is perhaps restricted by the budget: after the first two episodes there's no new elements added, and instead the story works itself out via the established situations.

This said, it's only a four-parter, and the many situations established could fill an episode several times over. But after being teased with multiple environments within the "miniscope", it's a slight shame we don't get to see more of them. Yet it's a great story within a nice – if perhaps unremarkable – era, easily earning a Top 5 placing here. As a comparison, if Carnival was placed in the rankings for the Hartnell, Troughton or Tom Baker eras then it wouldn't make the Top 10.

One notable change during the Pertwee era is that it introduced the practise of recording stories out of broadcast order. It first occurred with The Sea Devils being shot before The Curse of Peladon and shown in the reverse order, and continues here, with Carnival and Frontier In Space shot before The Three Doctors. Although rare at this point, it largely became the norm from the Tom Baker era onwards.

Speaking of behind the scenes details, then while Carnival has a fairly famous working title of "Peep Show", which was rejected because of its adult connotations, less publicised is that it was originally pitched as "The Labyrinth"/"Out Of The Labyrinth" in 1971.

One of the issues with discovering details of Doctor Who is that while the show has been very well researched, any recollections from the people who worked on it can't be taken as definitive as they're reliant on decades-old memories. Only when archive evidence of something being written down is presented can a "fact" be really regarded as "proven".

An example here is the quite terrifying roar of the eerie monsters of this tale, the Drashigs. On one of the two commentary tracks for the story, Brian Hodgson recalls it being a combination of one of his corgi dogs, his own voice, and possible stock sound of the Australian butcher bird, all mixed and electronically treated. However, Barry Letts remembers it as being a motorbike skidding being played backwards. One thing all agree on is that the teeth of the Drashigs are a result of real dog skulls being used to make them.

The Curse of Peladon is an example of a story having a certain "x factor", which shouldn't work, but does. It contains the silliest aliens up to this point in the series, yet with a "whodunnit?" plot, a nice closing plot revelation and the general atmosphere, it's a far better story than it has any right to be.

It may also be down to nostalgia, too. The Anorak Zone is pretty ancient, so was alive when Jon Pertwee was the Doctor, but far, far too young to engage with any of the show before mid-Tom Baker. However, there were repeats: Carnival of Monsters and The Three Doctors were repeated in 1981 as part of "The Five Faces of Doctor Who", while this story was shown again in 1982 as part of "Doctor Who and the Monsters". It produces a warm feeling, even if you perhaps know that it's nonsense.

Note that Jon's Doctor starts to become more pleasant from this point onwards, an eccentric uncle rather than a constantly angry, spiky character. While it does make it easier to watch him, it also shaves away the edge from his interpretation of the Doctor, and ushers in a "cosier" era of the show. It also marks a shift towards overt use of stunt doubles for Jon, with the "slow fighting" of the first two years giving way to Terry Walsh with a grey rug on his head.

One last mention of the notion of politics in the series. Fan theories align this one to the UK joining the EEC, but that would again just be "something in the air", rather than an overt reference. The UK entered the EEC in January 1973 - although obviously discussed beforehand, Brian Hayles was pitching the outline to this tale in March 1971. The fact that the UK signed the treaty to enter just one week before the serial aired is simply incredible good fortune. Having said all this, Barry Letts describes the Peladon stories on the commentary to Carnival of Monsters as "slightly political". Barry mildly contradicting himself in the Carnival commentary is touched on further in the next entry...

There's very much a certain "punk rock" mentality towards Terror of the Autons, where some of the sets aren't even built and have people acting in front of CSO'd photographs, and the violence is pushed to the extreme. People get choked to death by living armchairs, toys strangle people and a new companion is almost asphyxiated. Barry Letts even confesses on the commentary track that "I think, probably, we did go a bit too far on this occasion."

It's a wild ride that introduces three new characters. There's the aforementioned new companion of Jo, with Katy Manning actually putting on the high voice as a character choice. Jo also gets a potential love interest with the new character (though he's supposed to have been there before) of Captain Yates.

Ian Marter was also up for the role of Captain Yates and the reason why it was eventually given to Richard Franklin varies according to reports. On the commentary track for The Mind of Evil Barry Letts says that he went for Franklin as the final choice because: "Why I liked him, is he's a good actor, but wasn't obviously a soldier." It was ironic that Franklin actually had been an acting captain in real life, but the nature of his performance meant that romance angle with Jo never really worked out.

Yet on the commentary to Carnival of Monsters, which features Ian Marter in a guest part, Barry says that Marter was given the role but wasn't available for the schedule, so they held further auditions for the part. It's possibly a coincidence that Barry said it on a disc that featured Marter and didn't feature Franklin, and the reverse, and could just be unclear memories.

The last new face to be introduced is the Master, with Roger Delgado's charisma almost off the scale in this first appearance. The idea of an "evil" counterpart to the Doctor isn't an especially strong one, as it means the Doctor largely has to be overtly "good" for the contrast, something that shaves off a dimension or two of the lead character. There's also the problem of what really motivates such a character?

Such matters are made infinitesimal by Roger's superbly vicious first take on the character, and it's to his immense credit that what is, on paper, a thin part, is made into an unforgettable classic character. There's very much an argument that the character should have ended with the Pertwee era - although he was largely absent from Tom's - but if the character has been overused and done to death, it's because Delgado made it such a strong and enticing one, all those years ago.

One bit of trivia is that this is only the third story (after Planet of Giants and The Tomb of the Cybermen) to have maintained or increased its audience each week, not counting two-parters. With Who being very much a "first night" programme, audiences traditionally dropped away after each opening instalment, and this increase in audience figures each week only occurred seven more times during the original run of the show.

Terror of the Autons has a certain perverse style that makes it top this ranking, even if it doesn't always have the plot logic to back it up. In the discussion on Frontier In Space it was noted that seeing these things more than once can help, and the foreknowledge that the ending is effectively pulled out of a hat can help you get used to it.

Even Barry Letts had his issues with the plotting of the tale, saying of the ending on the commentary track that: "We've got to have an ending, and unfortunately I think we rather failed on this. Bob Holmes's a very good writer, but [...] the Doctor persuades the Master to change sides, to change his mind, er... and it all happens in a split second. [...] Now it's ridiculous that the Master hasn't - it hasn't crossed the Master's mind up to that point, and yet we had... we accepted it."

Despite all this - or maybe because of it - Terror of the Autons has the feeling of a wild, unhinged ride. It tops the ranking here in a fun era.

If you'd like to treat me to a coffee for this look through the Pertwee era of Doctor Who, then the button is below. But if you don't, that's fine too, and I hope you've enjoyed the article.