A great adaptation of one of the more pathetic of all the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories, but one which almost caused a fight (apparently). According to David Burke, Brett was unhappy that the crucial meeting between Nancy and her long-thought-dead beau, Henry Wood, was due to be filmed indoors, rather than under the lamppost as it was set in the original story.

The director, Alan Grint, argued that the location made little difference and that it would cost unnecessary funds to carry out a nighttime shoot on a location which would require considerable set dressing. Brett, who had not only read the entire Sherlock Holmes corpus before filming on the first series began and who had also compiled a 77-page dossier on Holmes listing his tastes in food, tobacco, music, etc, was outraged by any deviation from the text and squared up to the director, demanding that no compromise was acceptable.

In a striking foretaste of the manic depression which he was to suffer from after his wife's death, Brett then collapsed in tears and apologised to everyone for his behaviour. It was a sign of Brett's professional commitment, but also his brittleness as a personality.

In the episode, he is matched by a wonderful cast of up and coming actors, such as Fiona Shaw and James Wilby as well as the marvellous veteran Norman Jones, who should be familiar to most readers in his three terrific guest roles in '70s Doctor Who - Khrisong in 'The Abominable Snowmen', Major Barker in 'Doctor Who and the Silurians' and Hieronymous in 'The Masque of Mandragora.' It's a slight story, largely resolved through flashbacks, but the quality on screen carries it.

Brett had only brought Holmes back from the dead as a promise to his dying wife and it may well be that this was a fatal decision for the grieving actor. Even more so than before, he subsumed himself in the part, spending breaks in filming alone and in character. The long passages of dialogue he had to recall and the intensely high standards of performance he had set himself began, eventually, to wear him down, even though he eventually found a close friend and carer in Linda Pritchard.

You can occasionally sense this in his performance in 'The Priory School', as he appears distracted from the whole affair and, as a result, the pace slackens at times. However, you can see why they wanted the director, John Madden, back for 'Hound of the Baskervilles', as the exterior filming at Chatsworth and the interiors at Haddon Hall are dripping with atmosphere and the quality of the production has been cleverly realised on screen, with Patrick Gowers' lovely choral score adding a unique element. This was a time when the BBC, torn asunder by internal and political battles, relinquished its long-held crown for period drama to Granada (the BBC won it back in 1994 with Andrew Davies's Middlemarch).

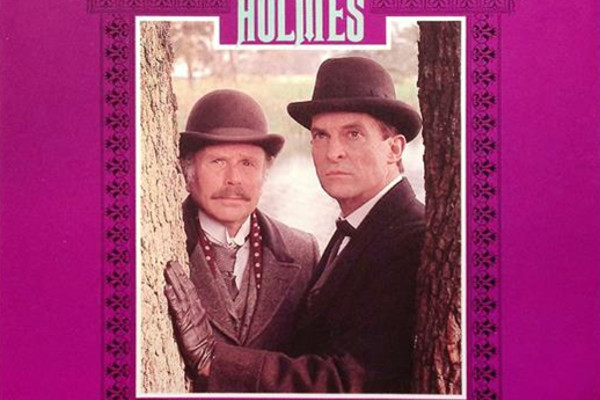

It is quite a tribute to Edward Hardwicke to note that this was his first performance on taking over the role of Dr Watson from David Burke, as it seems by this point in The Return, that he and Brett have built a strong rapport with each other. Burke's Watson was sometimes a little too in awe of Brett's Holmes, but Hardwicke's Watson is more of an equal - he may not have Holmes' brain, but he is less unstable, less impulsive and certainly more reliable than his co-tenant at 221B.

There's a lovely scene where Anne-Louise Lambert's character is describing how her husband became an alcoholic and Peter Hammond, thankfully still in a restrained mood in his series debut here, pans to Brett who smiles ruefully in recognition of the symptoms of the addict and then cuts to Hardwicke who recognises that Holmes has finally realised the danger than his cocaine use has put him in.

And Brett at the end, concluding that his findings have incriminated a victim of domestic abuse and her saviour and consequently unwilling to pass these onto the police, clashes with Hardwicke's Watson who is 'uneasy' that Holmes has arrogated to himself 'the duties of advocate and judge' in a lovely closing scene that is underplayed to perfection.

Possibly this one is a bit of a cheat on my part, as this wasn't a television series - rather a theatre production, written by Jeremy Paul and performed by Brett and Hardwicke at Wyndham's Theatre in London for a year before touring the country until the end of 1989.

In some ways, I resent this, as it delayed the filming of The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes until 1991, by which time Brett's health was beginning to deteriorate seriously - and, having seen the production at Wyndham's, I can see why, as it was as physically demanding a role as I have seen on stage (with perhaps the exception of Henry V).

Brett had to exaggerate the subtlety of his television portrayal and did so by making the character restless, energetic and somewhat manic (which no doubt had an effect on Brett's own fragile mental health, one fears).

The play is, in the first half, a series of vignettes of Holmes and Watson's most memorable moments, culminating in Holmes' dramatic reappearance from 'The Empty House.' Watson duly faints - and the curtain falls. In the second half, however, Paul takes inspiration from Nicholas Meyer's Seven Per-Cent Solution and has Holmes revealing to Watson that Professor Moriarty never existed and that he invented him in order to bring a network of criminals to justice.

It should have been ludicrous, but given Brett's stage training and his obsessive immersion in the character it was compelling and utterly enthralling. So what if it is not canon and contradicts what we saw on screen in 'The Final Problem'? It remains the best two-handed stage performance I've ever seen and I'm very pleased to include it so highly.

Abe Slaney. What a name - and what a great performance (and quite an accent) from Eugene Lipinski, when he finally appears. Yet despite him and the marvellous Tenniel Evans, it is Brett and Burke who own this episode. The sequence where Watson secretly uses Holmes' code books to try to break the central cypher and then when Holmes allows Watson to explain the key to the mystery to the police, while Holmes looks on with amusement, are priceless and speak of the fabulous chemistry that they managed to build in their portrayals of the great detective and his amanuensis.

The way the actors, scriptwriter and the director understand that on television, with its intimacy and immediacy, less is more is best exemplified by Burke's delivery of the line 'This is Sherlock Holmes' to the ignorant police inspector. Moffat and Gatiss would have had poor old Martin Freeman giving a speech about how much he loves Sherlock, though he drives him mad, but these artists trust their audience to understand the significance of their performances. O tempora! O mores!

I suppose the problem with this one is that it isn't really a 'proper' Sherlock Holmes story. No client at 221B, no intriguing mystery that leads to danger for an innocent (but plucky) victim (or a false accusation against a friendless character) and no moments of brilliant deduction for Holmes to demonstrate the power of logic.

The entire story is an extended chase as the heroes attempt to quash Moriarty's network, while Moriarty tries to kill Holmes. The characters have almost taken over from the format. But this is Arthur Conan Doyle's fault, neither Cox's nor scriptwriter John Hawkesworth's and one must have a Moriarty, if one is to have a Holmes.

And what a Moriarty Eric Porter gives us. In perhaps the greatest scene in the entire series, two heavyweights of the British stage confront each other and make their determination to end the other plain through gestures and glances and very few words. The rest of the episode is pure hokum from the Mona Lisa plot, which Hawkesworth has stolen from 'City of Death', to the Reichenbach finale, which is a bit of a disappointing brawl. At least David Burke gets to exit the series with his dignity still intact as he movingly mourns his lost friend with appropriate restraint.

Oddly, the set-up for the series finale is far more satisfying than the finale itself (this is often so - 'The Waters of Mars' is far superior to 'The End of Time' and 'Suffragette City' is much better than 'Rock'n'Roll Suicide'). It starts fairly ludicrously, with the bizarre tale of Jabez Wilson, who is so clearly being duped, yet seems incapable of realising it. Yet director John Bruce swiftly ups the ante with a marvellous scene on the Baker Street set where Holmes realises that all the gang wanted was access to Wilson's shop in order to dig a tunnel to the bank opposite. The light-hearted mood suddenly dissipates and a desperate struggle in the bank's vaults ensues.

The cast is marvellous - the great John Woodnutt, Broton himself, as an arrogant bank manager, Richard Wilson, in a deliberately ludicrous red wig, cast against type as a criminal gang member and Tim McInnerny as a typically duplicitous character. It is McInnerny's character who elicits Holmes' best line in the series: "his grandfather was a royal duke, and he himself was educated at Eton and Oxford. So Watson, bring the gun!" And then at the end, we finally meet the frustrated genius behind the plot - Moriarty himself - and we realise that Holmes has prodded a particularly dangerous hornets' nest this time…

Alan Plater's best screenplay for the series - the first in the series to be filmed - is an absolute cracker. There is a deep mystery in Violet Smith's encounters with a bearded cyclist as she returns every Monday to her role as governess in a strange household in Surrey. Plater brings out some of the best elements of the material from the original story - Holmes' exasperation with Watson's bungling attempts to investigate, Smith's clear affection for her young charge, the odiousness of the villains, Woodley and Williamson, and, best of all, Holmes' pugilistic encounter in the pub with Woodley.

In the story, it is recounted by Holmes on his return to 221B, but here Plater has him take on Woodley, with an eccentric boxing style that has the pub's customers applauding at the outcome (my family and I did likewise on first viewing). It is full of action, despite a very thin plot, but just a little sad that they couldn't have made Violet a bit less of a wet lettuce in the final scenes. Barbara Wilshere made Violet into such a dynamic and feisty character, it was a bit of a shame that the drama had to make her into the archetypal Victorian damsel-in-distress at the end.