Produced by Budgie's Executive Producer Rex Firkin, broadcast of the series was badly hit by an ITV strike, causing it to be aired over the course of a year, and fading into obscurity as a result. Join me as I celebrate what was a planned release of the DVD by ranking its six episodes from worst to best... articles on Budgie are also available on this site.

Written by Alistair Bell, this episode sees Charlie in charge of a rival gangster's businesses while said gangster is in prison. Although the series was written as more of a spin-off show than a direct continuation of Budgie, it's sometimes difficult to ignore the changes made to Charlie's character in order to make the programme work. Just as Shameless retooled the villainous MacGuires as characters the viewers were suddenly supposed to root for, Charles Endell Esquire has Charlie softened into a far more avuncular, caring figure, prone to failure. In doing so, he practically takes the same function as Budgie himself, coming up with schemes to get himself back on his feet, only to be met with various disasters every episode.

As a result, the series is perhaps best enjoyed more in isolation, where it's easier to overlook small discrepancies like Endell's schoolfriends knowing him as Charlie (it being revealed in Budgie's "King For A Day" that his real name is Angus McIntyre) and larger ones, such as Charlie already appearing in a greyhound storyline, and knowing far more about the animals, in Budgie's "Glory Of Fulham".

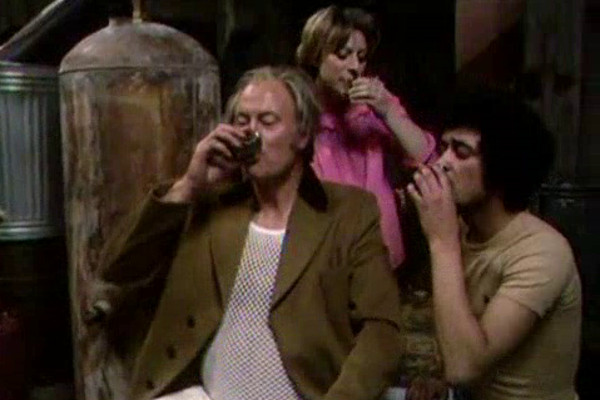

The real bonus of this episode comes around 47 minutes in, with Bill Denniston's line of "you're going to get what's coming to you" seeming to produce unscripted smiles from all three cast members in shot, and Denniston's voice cracking as a result. By all accounts, the cast had great fun making the series, and it's amusing to see it slipping out during a take.

In which Charlie attempts to make his own moonshine, with the aid of his two employees Hamish MacIntyre Jr (Tony Osoba) and Janet (Julie Ann Fullarton). Although fine, the duo don't generally get a lot to do in the series, something which would perhaps have been developed had STV decided to pick it up for a second season. Writer Terence Feely attempts to add to this relationship more than most, having Janet charmed and mildly flirting with Charlie, while Hamish watches with a look of jealousy.

Probably the main issue with the series is that, while none of the six episodes are actually bad, most of them tend to write Charlie as over pontificating, a verbose windbag that he never was in Budgie. Although Willis and Hall gave him some pithy one-liners (the final episode of Budgie sees him describe the titular character as having "the sexual proclivities of a nomad jackass, coupled with the moral fibre of a blue-arsed baboon!"), he also spoke in a naturalistic way for much of the time, and was never as self-consciously wordy as he is in his own show.

Probably the most unorthodox and unlikely episode of the bunch, Robert Banks Stewart here creates a world where Charlie wants to help a young pop band achieve success. Although there's an underdeveloped subplot where one of the band turns out to be his son, motivating Charlie's interest, it's a somewhat unusual concept for a series of this nature, the kind of thing would be more likely to feature in a Look-In comic adaptation than the series proper.

The programme is blessed with a significant amount of location filming, and although the credit sequences look cheap, the series as a whole stands up well in production terms. Yet look out for a "mob" of pop star groupies... made up of six extras. Also of note is a rare piece of meta referencing, with Charlie going to go STV to try and get his band on air, and asking to speak to "Big Brian", Brian Izzard... in real life, the producer of Charles Endell Esquire.

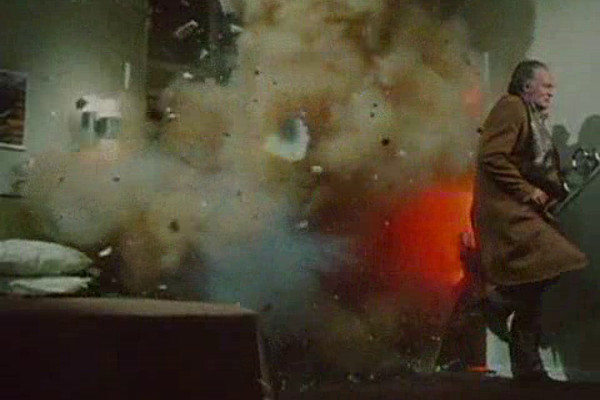

The underlying plotline of the series is Charlie, released from prison, trying to get back on his feet in his old home town of Glasgow. This particular episode ends with the main gangster in town believing that Charlie has not only double-crossed him, but has filmed his underage daughter for pornographic movies. Such an event would realistically see Charlie's death, but instead just sees him dumped into a building site for comedic purposes.

Such events can lend towards drama, with Charlie having to start all over again, his life in danger at every turn. But with his physicality toned down, and him repeatedly under threat from his criminal peers, it does rather undermine the character and take away his dignity. Despite this, this second episode, written by Bill Craig, does contain some memorable scenes.

The final episode of the series, written by Jeremy Burnham, the co-creator of Children of the Stones, which had starred Cuthbertson two years earlier. Although a fine episode to bow out on, there's perhaps no greater illustration of how the character had been softened than the final shot here: Charlie, surrounded by adoring children, suggests he buys them all a big party.

One of the series' biggest strengths is the well-developed female roles in Charlie's old flame and his probation worker. Although they don't always get a lot to do (particularly Annie Ross as his ex, Dixie), they're far more three-dimensional than the mute Mrs. Endell from Budgie, who was nevertheless a great joke character. Sadly, whatever the relative merits of this episode or lack thereof, the series was never given a real chance: the programme premiered in July 1979, but schedule disruptions meant the last two episodes had to wait until June 1980 before they aired.

In an interview with the STV website, Robert Banks Stewart stated that he hadn't had much involvement with the series beyond the two episodes he wrote, this one and Slaughter on Piano Street. Scottish Television Productions had the idea to bring the character back in Glasgow, with his creators Willis and Hall feeling that they didn't know enough about Scottish culture to write it.

The necessary machinations used to bring Charlie back after seven years off-air do undermine the character slightly; not only has most of his money been taken in a divorce settlement from Mrs. Endell, but his constant victimisation at the hands of other criminals makes him far softer and vulnerable than he ever was in Budgie. Even having him spend a term inside prison detracts from the Machiavellian character he was in his original appearances, though such decisions are perhaps necessary to bring the character to the screen in his own show.

Although a reasonable series, containing no outright awful episodes, this opener is, sadly, the only one that shows genuine promise. Although nowhere near as artistically successful as Budgie, there's less here that dates the programme, although Endell's insistence on calling Hamish "chocolate drop" and "tar brush" give his character a previously-unseen element of casual racism. Yet with this first episode there's a more dramatic edge, and a sense of genuine danger. Sadly, such promise was diluted for "caper of the week" storylines which, while entertaining enough, make Charles Endell Esquire more of a "take a look if you get chance" programme rather than a "must see".

Lastly, credit must be given to two previously-unheralded elements of the programme: what appears to be a hair piece on Cuthbertson's head, far more prominent than in Budgie and deserving of its own credit; and the theme tune, sung with off-key abandon by Cuthbertson himself, and veering between "unlistenable" and "twisted genius".