The first official pilot episode for The Twilight Zone, it follows The Time Element, which was eventually screened as part of the Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, and Serling's script "The Happy Place", which featured state euthanasia and was rejected by the network.

Where Is Everybody? features Earl Holliman as a man alone in a deserted town, breaking down through isolation and loneliness, themes which were touched on again, more than once, in the programme. It's hard to get much intrigue out of a man by himself for twenty minutes, but director Robert Stevens (Walking Distance) does his best with the material. It's a solid enough episode, hence the relatively high placing, but ultimately it's an "against type" instalment even in an anthology series like the Twilight Zone. Most episodes settled into two-handers of dialogue... this is one that tries to get a single actor to tell a story.

A suitably sombre and bleak tale of the Second World War, whereby a Lieutenant is haunted by the fact that he can see a light on the faces of those about to die. In an earlier article, I'd given praise to an episode of the 2002 revival series, Into The Light, forgetting this instalment and just how heavily it had borrowed from it. It's an indication of just how good this opening season is by the fact that the ranking is already presenting episodes as good as this and we haven't even entered the top twenty...

One of the most amusing and charming elements of the original series is its pretense that its leading male characters are all of a relatively young age, with "36" (as here) seemingly the default. Occasionally the actors are that approximate age, and people just seemed to look older back then, but more often than not it's someone like Howard Duff, then entering his late forties, playing the part.

Duff plays Arthur Curtis, a businessman who wakes to find that his entire life is just a movie. It's a simple but effective conceit, and, while done many times since (including in at least one show covered on this site, UFO) it was possibly a novelty then. With 156 episodes, the series inevitably repeats some tropes, and the concept of an identity crisis did resurface in season three's Person or Persons Unknown, and in the next entry (written, as with the episode here, by Richard Matheson) A World Of His Own. In all instances it was a solid concept, a good fit for the programme.

There are two major differences between season one and what followed. The first is that Bernard Herrmann composed an ethereal theme tune, and the more familiar "do do-do do" theme by Marius Constant didn't appear until season two (though occasionally appears on season one episodes, post-dub, in repeats). The other is that Rod Serling only appeared after the end of each story to introduce the following week's tale, his introductory narrations to the episode being verbal only.

Although undoubtedly one of the coolest men who ever lived, Serling was nervous in front of the camera at first, and it showed. Smoking a cigarette in only six of the intros, he appears uncomfortable in many of them. There's a nice little wink at the end of Mirror Image

but generally he's fairly ill-at-ease, although still charming. (Interestingly, although he describes The Big Tall Wish as "very, very special" it's one of just two - along with The Chaser - where he doesn't name any of the actors to appear in it)

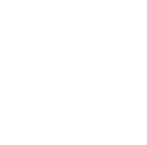

A World Of His Own, the season finale, changes everything. It's the first time that Serling actually becomes part of an episode, rather than appearing after the end/before the final credits. Although his surprise appearance was somewhat given away in the previous week's intro ("... even this kooky writer gets into the act") it's still a fine moment, wherein a story about a writer who can create people out of thin air using a dictation machine - one of the series' finest comedy episodes - reveals that Rod himself is fictional, too. Rod actually appears energised by appearing alongside the actors, and far more at ease with the material. It led into season two, wherein he'd appear within each episode, narrating onscreen.

As the series went on, Rod Serling wrote fewer of the scripts, allowing other writers to come on board. This was understandable as the workrate must have been immense, and even in the season with his lowest output - season four - he was still writing almost 40% of the scripts.

Season one sees over three quarters of the scripts written by Serling, a massive 28 of them. This one and Execution were based on short stories by George Clayton Johnson, who would come on board the following season as a writer. Eventually Johnson completed scripts for four highly memorable episodes - A Penny For Your Thoughts, A Game Of Pool, Nothing In The Dark and Kick The Can - as well as providing the story for the final season's Ninety Years Without Slumbering.

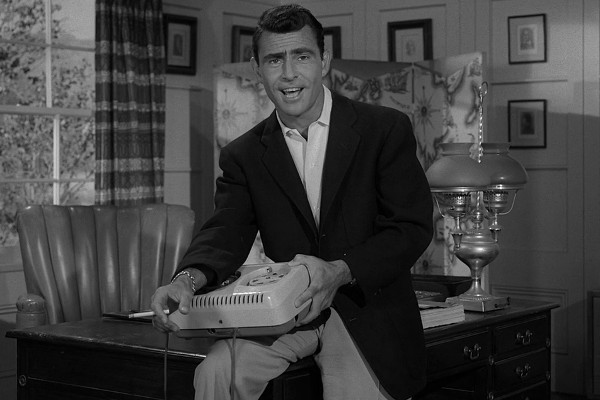

The wilfully abstract style of the original series can be enjoyed to its fullest during the opening moments of this episode; with all the events captured on sets, there's a mix of Dutch angles, surreal light displays and even a sign for a lady in a bikini in what is an abstract depiction of night life, rather than a literal one. With a score by Jerry Goldsmith, this tale of a small scale crook with the ability to change his face gets off to a classy start.

Jack Warden's first appearance in the series as a man sentenced to fifty years on an asteroid after committing murder. Serling always has a love for wordy dialogue, and Warden's blue collar antagonist talking about the inside of his mouth being "like gunpowder and burnt copper" is one of the charms of the series... a series where even the coarsest of characters are capable of waxing lyrical. Complicating matters is a robot brought to the asteroid to alleviate his loneliness... a robot in the form of Jean Marsh.