The Celestial Toymaker is a fairly rare example of a story that had its reputation changed over the years. Amongst fan circles, the standing of stories is often more-or-less set in stone, and very few of them get widely differing receptions over time. Those with very long memories might recall a time when Kinda and The Ambassadors of Death were lowly regarded, but these are exceptions to the rule.

The Celestial Toymaker is a story that had its stature changed with the release of its sole remaining episode (part four) into the home video market, and the release of the soundtrack of the existing episodes. The Hartnell era predates most of current fandom, and so for years the reputation of these stories solely rested on Target novelisations and the word-of-mouth of older statesman fans. To this end, The Celestial Toymaker had, for many years, the reputation of a minor classic.

In 1998 Doctor Who Magazine revealed the results of a reader survey, completed after the remaining episode had been released on VHS... it came 64th out of 155 original series stories, which was a drop from its perceived status, but still fairly respectable. However, the story has continued to drop, possibly coincidentally, after wider release. The audio soundtrack came out in 2001, and the existing episode was put onto DVD as part of the Lost In Time boxset in 2004. A 2009 DWM survey saw it plummet to 110th place (old series stories only), and in 2014 this had dropped even further to 121st.

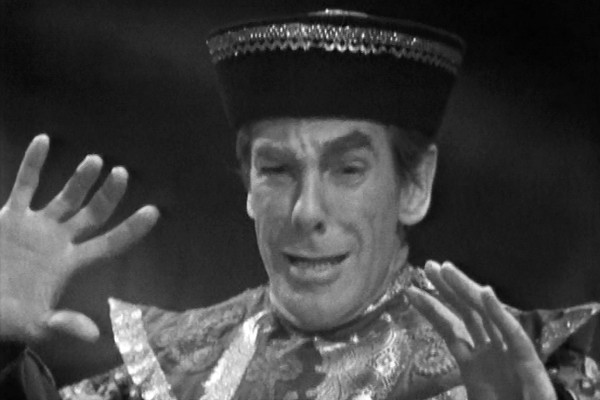

Narratively it does drag, as Hartnell was on holiday for the middle two episodes, so the story – a malevolent man in a Mandarin outfit makes Steven and Dodo take part in games like a sadistic, faintly irritating Adventure Game - does tend to get stuck in a "holding pattern". There's also Steven's out-of-character threats of violence, and the hugely contrived resolution, which sees the Doctor become a master impressionist-cum-ventriloquist in order to resolve events... not, amazingly enough, the last time this would be used as a plot resolution in the series, as those watching Tom Baker in 1976 could attest.

The serial was very much the work of two separate regimes, as producer John Wiles wanted to use the story to recast William Hartnell, and, with this vetoed by up high in the BBC, he quit, followed by his script editor, Donald Tosh. The eventual serial was made under new producer Innes Lloyd and script editor Gerry Davis. Tosh and Davis worked heavily on the story, but due to contractual obligations and disagreements, both of their names were removed from the credits, and it went out under the sole name of original writer Brian Hayles.

The character of the Toymaker was due to return against Colin Baker's Doctor, before the series was put on hiatus and the story scrapped. By this time the mysterious Toymaker was regarded as something of a more mystical, supernatural figure, like one of the God-level characters later introduced later in the series. And, while this does fit with the serial's discussion of the Toymaker being an immortal who has lived for thousands of years, it's striking that in the DVD commentary for The Time Meddler, Donald Tosh states that the Toymaker was originally conceived as another of the Doctor's own race.

Finally, the question of racism has to be addressed, as this story has been heavily criticised in fan circles over the past few years, with the suggestion that the Toymaker is supposed to be (white face) Chinese. This comes about from the knowledge that the word "Celestial" was also an archaic word for Chinese, something that wouldn't be lost on viewers of HBO's Deadwood (and does, in fairness, find its way into Doctor Who's problematical 1977 story The Talons of Weng-Chiang).

This is really a grey area, whereby the title of the character was decided upon before his Mandarin appearance, and the vast majority of fans had taken it on face value: the "celestial" with its far more well-known meaning of cosmic, and the character simply someone who enjoyed dressing up as much as he enjoyed his games. Yet there's also the clipped tones the Toymaker uses to direct his Trilogic Game to make computerised moves. As the Toymaker speaks in a RP English accent for the rest of the time, it suggests that he's not supposed to be Chinese, and that, as the Doctor explicitly states in the last episode, the Game would only obey instructions if the Toymaker delivered them "in a certain tone of voice".

This does, however, bring about perhaps an even more disturbing suggestion that the Trilogic Game – which is Chinese in origin – would only respond to a stereotypical "Chinese" voice, like the Toymaker was the Jason Spencer of his day... if, indeed, that's what he was doing. (While this site would never discourage or criticise fandom from discussing such issues, or disregard another's work, it must be noted that this theory originates from a series of critiques that take elements of the Hartnell era with crushingly literal interpretations of phrases... The Daleks' Master Plan features a line where the Doctor is referred to as looking like he comes from Earth because of a "disguise"... this is read at face value as a character, Mavic Chen – who couldn't possibly have known anyway – stating that the Doctor's entire body is disguised from its real, alien form, rather than the plain inference that the "disguise" is just that the Doctor dresses like he comes from Earth).

Then there's the use of the N-word in episode two, as part of the "eeny meeny miney moe" rhyme. What's shocking today is that it's used so casually, which is often suggested to have been acceptable at the time. Such a statement is questioned by elements of fandom, but the real problem here is conflating UK culture of the time with its US counterpart. When the US was screening Roots, the BBC were screening The Black and White Minstrel Show, and the N-word appeared in many UK television series without note, including the same rhyme being said in an episode of Dad's Army over six years later.

The list of British television programmes to have used the word is so great that it would require a whole article to itself, and the more sophisticated of them used it to satirical effect, including Monty Python, Fawlty Towers and The Young Ones. But to suggest that British society of the 1960s had gone beyond such matters, or even really understood, en masse, the offensive nature of such a term, isn't quite true. This was, after all, a cultural society that had the golliwog doll (seen in stills of this story) still in children's bedrooms until well after the 70s, and a jam manufacturer featured "Golly" on its jars until as late as 2001. To pin the accusation of racial insensitivity solely on Doctor Who is to not understand the entire fabric of UK society... it may not have always been a proud history, but it was the UK's history nonetheless...

The vast majority of the highest-ranked entries in this article are historicals. It's not just a question of the production on the science fiction stories, but also the writing and performances which stretch towards "pulp". Put in the simplest terms, then most of the historical stories can be watched today and fully appreciated for how intelligent they are... whereas many of the SF ones can look dated and patronising to the audience, more "Buck Rogers and ray guns" than credible speculative fiction.

The Ark has a terrific conceit, whereby the narrative for this four-parter is split in half; after two episodes the adventure appears to end... before the TARDIS returns to the same location, but 700 years later, and the crew discover that alien slaves have taken over the human race. While this is questionable in what it suggests as a political metaphor, it ends peaceably, but the innovation of the idea isn't supported by the guest cast or the script. This is, after all, a story with the line "Take them away to the security kitchen."

Michael Imison felt that Doctor Who was beneath him as a director, and so devised many overtly complex sequences to show his worth. While this led to overrunning in recording sessions, the evidence is onscreen, breaking the allocated £9,900 budget for all four episodes by £1,259. There was also a significant break from the usual "as live" filming process, as the final episode was shot out of sequence... something extremely common in television now, but rare for the time, certainly for a low-budget series like Doctor Who where editing cost additional money.

Doctor Who has always had problems with a lack of female writers, and even though Verity Lambert was the first producer on the programme, this didn't bring more female talent behind the cameras, with the first female director hired only after she'd gone. Although Lesley Scott gets a co-writer credit on this serial, along with her then-partner Paul Erickson, it's generally accepted that only Erickson wrote it, and the co-credit was his request. With this in mind, it wasn't until 1983 (Enlightenment by Barbara Clegg) that a female writer was involved in the series. Even with the new version of Doctor Who, the problem persists – just 8 out of 130 "New Who" stories have been written by women from 2005-2018.

Yet while The Ark starts off fairly well, the final episode is something of a disaster despite best attempts. It's a shallow viewpoint to condemn the story on something as simple as the Monoids talking, but when they do – with the voice of Zippy from Rainbow - it takes what was already a tenuous "alien" creation down towards the realms of parody. The Hartnell era must be praised for avoiding many of the good/evil tropes of later series, and crafting aliens that were simply different species with philosophies of their own, but it's notable that very few of them were deemed successful enough to bring back in the more streamlined "monster of the week" eras that followed. All of which is to say nothing of the invisible aliens with super strength...

The Ark has many problems, but, if the final conclusion is that it's a bit rubbish, it's at least entertaining rubbish. There's also the reuse of Tristram Cary's brilliant incidental music from The Daleks, and it's hard not to be impressed by a serial that actually creates an entire jungle, even if this will always be only the second most-famous instance of Peter Purves with an elephant in a studio.

Mission To The Unknown was the final production of Verity Lambert, acting as both a promotional "teaser" to the later Daleks' Master Plan (which she commissioned, but did not produce) and a chance for the regulars to have a week off.

As it's just a single instalment, it's perhaps, not unnaturally, the most "reconstructed" missing episode. While 44 of Hartnell's episodes are still missing to date, the soundtracks to them all exist, thanks to fans tape recording them on transmission. These recordings are married with commissioned "telesnaps" to produce an idea of what the episode would have looked like. While the reconstructions got more sophisticated as greater technology became available, these are still only a rough approximation of the real thing, and so guess work must be used when ranking them among the existing episodes that can actually be seen.

Probably the most famous Reconstruction group was "Loose Cannon", though other groups also existed, such as "Joint Venture", "A Change of Identity" and "Materialising Tardis", and all of these groups deserve praise for their efforts. To avoid copyright, the group shared their versions freely, save for the price of postage and a VHS tape, and gave pleasure to many, The Anorak Zone included. Mission to the Unknown had several attempts by several different groups, with at least six separate recons being passed between fans. All are creditable, but special mention must be given to Loose Cannon's reuniting of the cast for a special feature, with a 70 minute meeting between Edward De Souza, Barry Jackson and Jeremy Young.

In terms of trivia, then much debate has gone into what the actual titles of the first 25 stories actually were. These 25 stories went by individual episode titles, with overarching, "story" titles for each narrative not seriously considered... all of them went by various different, non-committal names at the time they were made, such as "Serial A" or "Dr. Who 1". However, research by fans has brought to light several titles which are largely considered "official", despite not appearing on the various VHS and DVD releases. These titles have been generally avoided here, simply because not only is it difficult to get used to these relatively new titles (established in fan circles for a mere 30 years) but also because they're often unwieldly. This episode was named onscreen as Mission to the Unknown, but that's the episode title. The story overall (which... consists of just one episode...) was titled Dalek Cutaway on BBC documentation.

Other titles, such as "The Massacre of St Bartholomew's Eve" (The Massacre) and "100,000 BC" (An Unearthly Child) have also been dropped from this listing. While An Unearthly Child isn't a fully satisfactory story title, given that it only really describes the first of four episodes, titles like "100,000 BC" are more internal documents from the BBC, there to sell the stories abroad, their intent not for fans to debate years later. As stated before, this particular story under discussion was packaged to foreign broadcasters as "Dalek Cutaway", but this is more of a description of the contents rather than an intended title for use, just in the same way The Dalek Invasion of Earth is never referred to as Daleks II. Lastly, there's also the confusion that the first Dalek story was almost certainly intended to be called "The Mutants"... but this has been dropped, as the title was later used for a Jon Pertwee story...

The story to introduce Vicki, a kind of proxy Susan, who does at least charm by trying to not to laugh at Hartnell's fluffed lines. As with The Dalek Invasion of Earth, The Rescue forces the programme towards science fantasy, as opposed to science fiction, by giving viewers another silly monster: Sandy the Sand Beast. The thing is hilarious to look at, yet oddly lovable, but is killed by Barbara who doesn't realise it's harmless and that Vicki treats it as a pet.

The TARDIS crew inexplicably scold Vicki for being "unreasonable" after she dares to be upset when a woman with hair like a motorbike crash helmet blows a hole in the side of her pet at point blank range. Later Ian, not destined to become a counsellor, waves the exact same weapon in Vicki's face, assuring her he'll use it to protect her, while the Doctor demands she apologise.

Vicki is kept prisoner by the demands of Koquillion (who Ian calls, troublingly for a family show, "Cocky Lickin'"), played by a strong guest actor in Ray Barrett. Koquillion, a threatening alien, turns out to be the alter ago of Bennett, Vicki's insane co-inhabitant of her crashed rocketship. Not even a fully-grown adult, Vicki left Earth in 2493 after her mother died, and while in flight her father was murdered. Barbara kills her pet, and, when she finds out her only trusted companion was really a psychopath who was behind her father's death, it's the end of a less-than-stellar day for her. Yet somehow she cheerfully joins the TARDIS at the end, making her less of a realistic figure than Susan, given that such events would have put most in therapy for years.

It's all silly but humorously watchable fluff, hard to rate in circumstances such as these. The real bonus is the return of music by Tristam Cary, bringing back his doom-laden theme from The Daleks. Cary composed for other Doctor Who stories - Marco Polo, The Gunfighters, The Underwater Menace and The Mutants - but this particular theme was reused several times. Viewers could hear it again in The Daleks' Master Plan, The Power of the Daleks and, mentioned previously, The Ark, and it really is a striking piece of work.

The most significant element of the story is that while, post-Susan, Verity Lambert might take her finger off the button marked "quality control", Hartnell's Doctor is allowed to show more warmth and humour without a granddaughter to worry about. Hartnell may ham it up a bit in his more "humorous" persona, but he can time a joke, and it gives a lie to the misconception that the first Doctor was just a "grumpy old man" who was unapproachable.

Lastly, lovers of anally retentive trivia may note that Ian says he let himself into the TARDIS with the Doctor's key during the climax... in The Daleks Susan claimed that it was a special lock combination that would be destroyed if not opened correctly. So either Ian got lucky, or the lock was since updated... or Susan was lying?

It's hard to say if the ultimate fate of the Doctor was to live in a universe where everyone knew him. Even as early as the third Dalek story, the Daleks were aware of the TARDIS crew and plotting to trap them. Despite being able to travel an infinite universe in any time, knowledge of the title character soon spread, almost as if every galaxy in every age was switching on a TV set each Saturday at 5:35.

By the time of season three, Doctor Who was shifting to become less about a scientist having hapless adventures, and more about the character righting wrongs and being acknowledged for it. The Ark has his legend being passed down 700 years through generations, while The Celestial Toymaker has him encounter a foe never seen before, but who has met him in untelevised adventures.

While this isn't quite the new series' fannish fixation with characters constantly telling us how amazing, brilliant and wonderful the lead character is (even the Doctor himself), it marks a turning point in the show. The Savages has a race of aliens who have been following the Doctor's travels, and want to praise him as a result. In a nice twist, rather than wanting to add serious fan worship, they really just want to steal his life force.

The serial was to be Peter Purves's last as Steven, staying behind at the end to rebuild the society of the planet. Never as overtly likeable as Ian Chesterton, Steven is often pig-headed, arrogant and aggressive... which, in many ways, makes him far more human. Ian is the companion that viewers would perhaps aspire to be... Steven is the companion that viewers are. Peter Purves took on a role in Blue Peter afterwards and became more known as a presenter, but he remained a committed ambassador for the series, helping out with interviews on the reconstruction videos from Loose Cannon (including this one) and recreating the character for Big Finish audios.

The serial plays with standard tropes by having an oppressed minority the white population (the working title was "The White Savages") and, like the first Dalek serial, it transfers the imagery of the oppressive races for metaphorical effect. Just as the Nazi symbolism of the Daleks saw them fighting against a blonde-haired, Aryan race, here the oppressors are black men... played by white actors in blackface. That such a thing wasn't regarded as troubling at the time can be gleaned from Patrick Troughton's semi-serious desire to play the entire role in blackface later that same year.

Nine of the Hartnell stories had some form of location filming, and while the shots taken in London for other stories may be more famous, The Savages is notable for basing itself so heavily around a quarry, something that would become almost synonymous with the series. Less than a minute's footage of The Savages currently survives in the archives, and what does was as a result of 8mm film of a TV screen, explaining why the image above is of notably lower quality.

Last points of trivia are that The Savages is the first story to discard individual titles for episodes, the writer mistakes "light years" for a measure of time, and the incidental music is, unusually, strings. Overall, The Savages has never been very popular in fan surveys, usually rated in the bottom forty, but it's hard to see (or hear) why... rather than being especially bad, the story is more guilty of just being simply okay.

Missing, save for a few clips, this is the penultimate historical of the old series. The Highlanders was made with Patrick Troughton, then the genre was scrapped altogether in favour of the monster stories which were more popular with the audience.

By this stage the series had abandoned all serious attempt at historical accuracy, and instead presents a lively, extremely violent tale of skulduggery and stereotypical smugglers. Villains are "black hearted", and the first major speaking role for a black actor is an eye-rolling stereotype going by the name of "Jamaica". Critics of Hartnell like to suggest that such things are symptomatic of the era, almost as if Hartnell had some domineering influence that wouldn't allow for wider parts for non-white actors, or that characters like Toberman, who appeared in the Troughton era, were three-dimensional representations. (A recent newspaper column also stated that Doctor Who was finally tackling its "race problem"... while later eras may have more to discuss in this area, such a view shows a lack of understanding in how television was made at the time, with far fewer minorities living in England, and consequently fewer non-white actors to choose from).

The subject of the first Doctor being "racist" is a somewhat contentious one, exacerbated by the new series recasting the part in 2017 with David Bradley and presenting him as being such. While Bradley gave a creditable take on the role, the script by Steven Moffat bordered on character assassination. A rather juvenile attempt was made to recast the first Doctor as a bigot, probably inspired by stories that Hartnell was one in real life. It's a very childish decision to write such a script, the new version of the series once more dripping with self-congratulatory disdain for the series that inspired it.

The old series of Doctor Who was generally made by industry professionals who, while caring about what they made, didn't have undue emotional attachment. The new version of the series has always been led by self-proclaimed fans of the original, and it shows. There's perhaps nothing more fannish than go to the time and expense of recreating the sets from Hartnell's last story, The Tenth Planet (despite casting an actor 7 inches taller than Michael Craze to play Ben)... then bringing back the first Doctor as an intolerant bigot.

Was William Hartnell a bigot? Those who suggest he wasn't, or that it was "of the time" are often slated as "defending" racism, but, as we've seen with The Celestial Toymaker, societal mores have changed. Even in the early 80s, director Richard Martin was giving an interview to a fanzine where he described Hartnell as having "worked like a white man". But expecting a man who was born 110 years ago and lived through two World Wars to have the same viewpoints as a person living in 2018 is fairly ludicrous.

Much of the talk of Hartnell's "racism" is alluded to without real context or citation. The most concrete evidence of such views actually comes from his own Granddaughter, Jessica Carney, who wrote the biography Who's There?: The Life and Career of William Hartnell and stated that he did express concerns about "foreigners", but that "all those loudly expressed opinions were contradicted by his behaviour on a personal level. [...] if he liked someone, they weren't a foreigner, they were a friend."

Many of the people who would have been likely targets of such views spoke of Hartnell's respect and professionalism, such as director Waris Hussein and actor Earl Cameron. Those who take Hartnell's views as a means to condemn him (which were, by most accounts, frequently challenged by his love for his co-workers of different backgrounds) are perhaps fortunate to have never had an elderly relative who had similarly old fashioned ideas.

Yet discussion of Hartnell's personal views always misses the main point, which is that, even if Hartnell was a racist behind the scenes and in his private life, the character he played wasn't. A man who responds "No, good gracious, no!" when asked if he's "English" and describes himself as "a citizen of the universe... and a gentleman, to boot." This was a creation who travelled round the universe suggesting that cultures learn to love one another... whatever was said in rehearsal rooms over half a century ago has been lost to time, whereas the message of peace and harmony that the Doctor espoused lives on.

For the record, the only references to race the first Doctor makes are as follows: he refers to a "Red Indian" with a "savage mind" in the opening story (possibly a specific "Red Indian" that he and Susan had seen, pre-series)... he refers, non-pejoratively, to a "Chinese child" in Marco Polo... in The Feast of Steven (the episode of The Daleks' Master Plan that's a broad, knockabout comedy) he remarks "This is a madhouse, it's all full of Arabs!". The same story, four episodes later, sees him concerned, again non-perjoratively, that there might still be "one or two of those Egyptians around" after they'd witnessed said Egyptians violently destroying Daleks. Quite a far cry from the time-travelling Alf Garnett that the BBC deemed fit to air on Christmas Day to over five million viewers.

In this particular story, he refers to "The blackest villain of them all", but it's the Doctor adopting the language of his captors in order to escape... more to the point, it's not a reference to race, but to the 17th century terminology of black being evil. In modern times it may seem slightly uncomfortable seeing a black actor being told he has a "black soul", but it really doesn't mean that, and if you're watching a 52-year-old episode of television and expecting it to be "woke"*, then maybe you've picked the wrong hobby.

And that's it. An actor who played the character for 129 episodes, and said nothing related to race – other than positivity and love – for 125 of them. The character played on screen by Hartnell, is, at least for anyone who'd ever had a grumpy grandfather, a charming and quite sweet individual. While he was undoubtedly "difficult" behind the scenes, fandom in general has seen fit to retool a man who died over forty years ago as "behind the standard of modern times", and largely eviscerate his reputation, and the reputation of his character.

While the first Doctor was written as slightly "behind the times" with his new, more modern companions, actually watching him (or listening to him) is a big difference from his reputation. The Hartnell era presented aliens in far more grey areas than the black and white "good and evil" depictions that followed, and yet for many modern fans, many of who haven't even experienced the Hartnell era, the only real "monster" in the series was the leading man. But watching him afresh, it's striking how sweet, charming.... and yes, grumpy... he could be, and the overriding desire is just to give him a great big hug.

* An example of the rapidly-changing nature of language here, as I used the term 'woke' almost as self-mockery when originally writing this article. In the five years since it was published, "woke" has become a derisive catchword of the right-wing, giving this little comment a different meaning to that intended.