While production photographs of the time may cast an image of elderly, pipe-smoking men, the majority of the writing staff were considerably younger than expected during the Hartnell era. While the average Doctor Who writer was a man in his 40s during the Troughton-Colin Baker eras, William Hartnell's scriptwriters averaged at a comparatively youthful 37.

Only three of the seventeen Hartnell writers had passed the age of 40, and so the series existed largely as a document of authors who had grown up during the war, becoming a very post-conflict series. Throughout the seventies, the series went on to explore the UK's role in a post-Empirical world, both informed by and reflecting the state of the nation.

By the time of the 1980s, the series had begun to stop and comment only on itself; monsters were no longer the fears of an industrialised England, but returning foes there to please its own self-knowledgable audience. While it did, in part, continue to use its stories to refer to socio-political events, these events were no longer inherent in the narrative, and so often had to be "grafted on", a "subtext" that lacked subtlety, leading up to the redundant notion of The Daleks appearing alongside fascists in Remembrance of the Daleks (1988), seemingly missing the point that the entire point of the Daleks was as a Nazi metaphor in the first place.

The new version of Doctor Who continued this trend, bringing the Daleks back in 2005 to much success, but with their origins and point long since lost to time. Consequently the overt politicising and dominant authorial voice of the writers in "New Who" can become gratingly overwhelming in its crass spoon-feeding of the viewership, a fact often lost on many vocal supporters of the new series, who frequently feel that criticism of the "tell not show" narratives of 2005-2018 equate to rejection of the values presented within, as opposed to rejection of their ham-fisted, "on the nose" method of delivery.

This is not to suggest that the original series was always a high benchmark of subtlety, however... Terry Nation, who was just nine years old when the Second World War started, clearly had personal horrors he unleashed on screen, though even as early as The Chase, "exterminate" was becoming a catchphrase, a means to its own end.

Directed by Douglas Camfield, arguably the greatest director of the series, The Daleks' Master Plan has a polish that the other Hartnell Dalek stories lack, and is an engaging "Boy's Own" adventure. Sadly, with half of the episodes being written by Dennis Spooner and having to stretch over a mammoth 12-part runtime, the latter half of the serial does fall prone to padding. Peter Butterworth reappears for three episodes as his brilliant Monk character from The Time Meddler, but adds nothing to the narrative other than filling out a few episodes, and seemingly forgets that he was only ever a "monk" to fit in with the 1066 background.

Spooner is such a quality writer that the episodes certainly entertain - and he can't have been so naïve to have not been deliberate with his "It came from Uranus, I know it did" line – but after the sixth episode, it all falls into a holding pattern, with no genuine narrative advancement until the final two episodes.

The story also feels like it lacks a true moral core, as the Doctor's largely neglected companion Katarina dies, and the Doctor and Steven associate with trained killers. It's almost like watching the Hartnell era script-edited by Eric Saward, with a nihilistic atmosphere throughout, more Terry Nation's Blake's 7 than his take on Doctor Who. The arguments between the Doctor and the various people he travels with (including Steven) also feel more like grating, childish squabbling than the usual amusing or intense confrontations.

While clips exist from the story, only three episodes – 2, 5 and 10 – exist in full. The second episode was the most recent of the three to be found, returned in 2004, and released onto DVD with a commentary track by Peter Purves, Kevin Stoney and designer Ray Cusick.

The War Machines throws the Doctor into the modern world for the first time, where nightclubs and short skirts abound, and he gets mistaken for Jimmy Savile(!) For such a self-consciously "hip" story, it had the oldest writer of the era, with Ian Stuart Black in his early fifties when the episode aired. (The only other Hartnell writers past 40 were The Web Planet's Bill Strutton and The Ark's Paul Erickson).

Despite discussion of which stories are "complete" in this article, it has to be acknowledged that some "complete" stories are still missing some footage. The Keys of Marinus and The Time Meddler were both censored when broadcast overseas, and, as the recovered versions were from these foreign broadcasters, they came with a few seconds missing. The War Machines is the worst affected, having come from Nigeria in 1984 with just over a minute of violence pruned between episodes three and four.

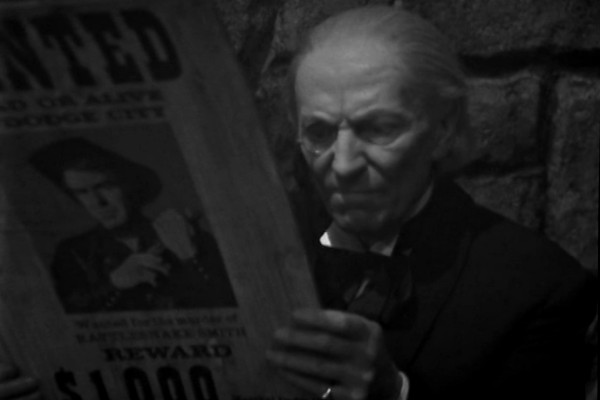

There's talk of Hartnell's performance deteriorating throughout season three, which is probably a handy excuse as not many people have seen it. Of the season three stories that still exist in their entirety, then The Gunfighters and The Ark aren't traditionally very popular, leaving this tale as the one that people would be most familiar with. It's clear here that Hartnell isn't always on top of the script (and nearly bumps his head in the fourth episode) but this is far from his worst performance, and he's able to edge around such stumbles.

The audios tell a different story. Following on from a second season, where Hartnell would seem to forget entire scenes, season three is generally a massive return to form, with some of his best-ever performances. Of course, it's possible that it appeared differently behind the scenes, or in rehearsals, but with the "as live" broadcasts to go on, this is definitely not the case of an actor in serious decline. Nevertheless, with location filming for the following serial, The Smugglers, his health struggled, and the decision was made for him to leave the series.

Michael Ferguson's direction is striking, and there's a faster pace involved. Viewed from this side of history, there's a temptation to say that the last three Hartnell stories (certainly this and The Tenth Planet) feel like Patrick Troughton stories before Patrick Troughton came into them, but then this wouldn't have been the case at the time. (Such a view also feeds into the oft-repeated idea that "Doctor Who" as we know it today only really began with the Patrick Troughton era, something said so often that it's come to be believed by large sections of fandom, despite being clearly untrue).

The actors behind Hartnell's last two companions, Ben and Polly, have a less comfortable onscreen chemistry with Hartnell than his other seven companions, all of whom had praised him as a co-worker, while acknowledging that guest actors in the series weren't always given the same welcoming treatment. Michael Craze (Ben) and Anneke Wills (Polly) were the only two to go on record as not having a great personal relationship with Hartnell, and it does show on screen.

Despite this, while Anneke is vocal in her negative impressions of Hartnell, it must be acknowledged that by this stage he was ill, and, despite this, she acknowledges on the commentary track to The Tenth Planet that "He was always very polite to me. He treated me like a lady, which was very sweet." With his clashes more with Craze, it must also be stated that – while bullying in the workplace can never be condoned – Craze does deliver a very one-note performance as Ben.

Such matters are alluded to by Carole Ann Ford in the DVD commentary to The Reign of Terror, where she states "I loved him. It's a shame that later on, you know, people have said... some rather uncomplimentary things about him, but he wasn't well of course, which nobody really knew at the time. He was just adorable, loved him." In regards DVD commentaries, then The War Machines was also the only Hartnell release post-2003 that didn't have a moderator on the commentary track, with Wills and the director alone.

For lovers of trivia, then the white window frames of the TARDIS get changed to blue in this story, along with the St. John's Ambulance badge being removed... but the location footage was shot before this happened, meaning they change colour depending on whether it's really outside, or just studio pretending to be outside.

While the story ranks very highly here, almost breaking into the top ten, the majority of its plusses are entirely superficial; welcome style surrounding a "killer machines" plot.

Considering the self-aware silliness that passes for much of the new version of Doctor Who, it's amazing that comedy wasn't something highly regarded by fans of the old series. Largely, this appears to be as a result of lack of exposure to the source material, and lack of instant access to other fans. In 2018 we live in an age where anyone not being impressed with the Master talking about getting an erection in New Who can be called a "hater" within seconds on Twitter... back in the 80s print fanzines and word-of-mouth were really all anyone had, along with zero access to the archives.

So it was that Jeremy Bentham's evisceration of this story was etched in fan lore with no one to challenge it, and even today its reputation is only now improving after more fans have had chance to see it. The serial was also slated as having the lowest audience figures of Doctor Who. While this is true of the Audience Appreciation Index (which were generally low for the series at the start anyway), this isn't true about the viewing figures.

While this was the lowest-rated story since An Unearthly Child (when the series was just starting out and growing its audience week by week), it marked a general downward trend of interest in the programme, and was followed immediately by three stories in a row, all with lower viewing figures. In the end result, the original series ended with 27 stories that had a smaller average audience than the 6.25 million that tuned into The Gunfighters.

Complaints that the story is historically inaccurate (it is) or that the American "accents" are generally appalling (they are) are missing the point... this isn't the Doctor landing in the real Wild West, but a deliberate pastiche of it. The story's postmodernism perhaps works better than it did at the time, as, while it's not exactly sophisticated, as such, it's a rendering of the material that goes beyond what audiences of 1966 would have been expecting.

Ultimately it's a story that's had such a bad reputation in fandom for so long that it's impossible to summarise it without referring to its rep. But the majority of critical reviews disparage for the story for what it isn't, rather than what it is. Rather like the DVD "trailers" which try to package every Doctor Who story as an action-packed thriller, no matter how slow or silly the actual content, The Gunfighters fails because it doesn't live up to what a section of fandom thought the series should be. But really, it doesn't "fail" as a serious story, because it's not trying to be one.

Jackie Lane's "Dodo" doesn't seem to get much chance to shine in Doctor Who, and often feels like the first "failed" attempt at a companion, with producer Innes Lloyd describing her as "a victim of circumstance". This impression isn't helped by her being cruelly removed from the series offscreen during The War Machines, but the problems are there right from the outset. She's the first companion to arrive without any real backstory, just running into the TARDIS by accident. Who she is, or what she's really about are never deemed important, and her character, such as it is, is often reworked to fit around whatever the plot dictated.

In many ways she's a prototype of the 70s companion, many of which were the archetypal "what does that mean, Doctor?" ciphers who could have been interchangeable. Matters also weren't helped by her first appearance having a Manchester accent, before it was vetoed and she went to RP thereafter. Like most of her tales, The Gunfighters sees her sidelined, but it does give Lane chance to show off her comic talents, and she fits more into this tale than arguably any other. And while Peter Purves perhaps overeggs the laughs a little too much, Hartnell seems rejuvenated by being pushed centre stage, and The Gunfighters is especially notable for how on form he is.

This is also, apart from the possible instance of a "Who's Who" gag in The Chase, the first appearance of the "Doctor Who?" joke, and the only time it was actually halfway funny. Speaking of trivia, then the Doctor claims "I never touch alcohol" in this story, despite the fact that we've seen him drinking fairly regularly up to this point, even toasting viewers in a manic Christmas episode. As the series got more child-orientated, this aspect of his character was largely shelved, as later Doctors did their drinking off screen, rather than on.

Lastly, the Ballad of the Last Chance Saloon may grate on some viewers as it appears as a narrative tool 27 times (not including when characters actually in the episodes, including Steven, sing it) but this wasn't a show made to be watched in one sitting...

It seems almost wrong for Hartnell's final story to be relatively lowly rated, but The Tenth Planet is not without some small problems. The first, zombie-like Cybermen with human hands and Zippyesque voices successfully skirt the line between scary and ridiculous. But while they specialise in killer lines ("there are people dying all over your world, but you do not care about them" is one of the series' finest) often they stand around delivering exposition.

Perhaps what's most distressing is that the Doctor takes such a back seat in his own final story. It doesn't help that Hartnell fell ill and is doubled in episode three, but even before that, most of the talk from the regulars is given over to Ben and Polly.

The story also marks a turning point for the series. While 1963-1966 wasn't exactly kitchen sink, gritty drama, there was an attempt to tell more realistic stories, after a sort, but from this point onwards the dialogue and characterisation of the programme generally becomes more stylised, playing with broader roles and melodrama.

This is not to suggest that the scripts of Terry Nation or The Space Museum gave us compelling, three-dimensional characters, but the programme began with people who were there as serious audience identification figures for the audience. This became somewhat lost when Steven and Vicki joined, being, despite good characters, from the future, and Troughton spent most of his first two years with characters who came from the past. Suddenly said companions became secondary to the plots, and their roles within events – as a general rule – became less significant.

Real-life scientist Dr. Kit Pedler had been brought onto the series as an unofficial advisor, and submitted ideas which led to the stories The War Machines, The Wheel In Space and The Invasion. He developed a close working relationship with script editor Gerry Davis, and together they wrote three stories: this one, The Moonbase and The Tomb of the Cybermen.

The two also went on to devise the series Doomwatch, but the most amusing thing about Pedler's legacy on Doctor Who is that, as a real scientist, he was ultimately responsible for some of the most unscientific stories Doctor Who ever did. This tale of a planet travelling through the cosmos makes The Dalek Invasion of Earth look like hard science, and, speaking of said story, it's tempting to wonder why Terry Nation didn't get more credit, given that the Robomen were the first "cyber" characters in the series.

The Tenth Planet, the first of many "base under siege" stories, was a pivotal episode in reducing the series' declining viewing figures, adding two million to the audience and pushing the series back in the 7 million range. In terms of chart position, it returned the series back into the Top Fifty for the first time in over four months, and, while the Troughton era wasn't able to keep the public as engaged as the series had at its first peak, it was able to keep the programme on the air.

It's the level of how significant the story is that pushes it so high in the rankings. Not only is it the first Cyberman story, but it's also the first regeneration story, leading to Troughton's take on the character. While the regeneration may seem to have come out of the blue somewhat, it does follow the Doctor taking a massive blast from the time destructor (The Daleks' Master Plan) and having his life force drained (The Savages), so it's no wonder his body became "a bit thin".

Despite many detractions, The Tenth Planet is a well-made, solid-looking production (at £11,814, it came in £844 over budget) and remains one of the most essential stories in the entire programme.

Not, strictly speaking, a "pilot" episode in the real sense of the term, this was the first take at the script for the first episode, An Unearthly Child. It was screened for series co-devisor Sydney Newman, who, legends say, simply said to the director "Do it again, Waris."

However, it is notable for several changes, including Susan as a much stranger, more aloof character, making rorschach tests and saying she comes from "the 49th century". Particularly notable is that she has no compunction with the idea of leaving the 20th century, and her love for Coal Hill School is said more as patronage to Ian and Barbara, rather than genuinely meant.

While Hartnell's character in the first story could hardly be classified as "warm", he's even colder here, and wears a contemporary jacket and tie, rather than the Edwardian outfit, although the trousers are still the same. In particular, his callous, sinister laughing at Ian when he realises he's trapped in the TARDIS is even more unnerving than what went out on November 23rd.

While such matters are largely just details, it does make you wish that a "second take" could have been done for the entire run in many ways... as it stands, only the first episode of The Daleks got a second version, and that was due to technical issues with the first. In the transmitted version of An Unearthly Child, the performances are far sharper, the pace slicker, and everything more assured.

Those looking for fluffs with the regulars won't find anything as striking as the TARDIS doors banging by themselves, cameras stumbling, or Hartnell's tactile relationship with Carole Ann Ford getting off to an awkward start as he accidentally touches her left breast. The final version of An Unearthly Child is arguably the best Hartnell episode of all... this first take at it is merely just pretty good.

The only incomplete Doctor Who story from season two, part one was found in 1999, but parts two and four still remain missing. The cod-Shakespearean script and blackface may trouble viewers today, but when Julian Glover and Jean Marsh are on screen together as King Richard the First and his sister Joanne, it's electric. (Amazingly, Marsh claimed that the best Doctor Who script she'd seen was Battlefield.)

While many discovered episodes have led to reappraisal of missing stories (such as 2013's release of The Enemy of the World), The Crusade is perhaps one let down by a discovery. Until then all that remained in the BBC archives was episode three, which is excellent. The rediscovered episode one is very good, but not in the same class... overall, it's perhaps a second-tier historical compared to the very high standards of many of the others.

The two existing episodes were released (along with the audio tracks of the two missing episodes) on a special Lost In Time boxset dedicated to the missing material. Episode three features Julian Glover in conversation with Gary Russell on the commentary track, revealing that Jacqueline Hill and William Russell would make guest casts welcome as Hartnell "wasn't very good at that", and describes him as "cold" towards himself and Marsh. Glover believed that a lot of Hartnell's perceived resentment was due to class resentment... one thing often forgotten about the first Doctor is how much of a performance the entire character is, even down to the RP accent, which is fake.

Also of note is that Glover mentions that he and Marsh wanted to explore the rumoured incestuous relationship between Richard the Lionheart and his sister, but this wasn't deemed appropriate material for the series. Rumours suggest that this was at Hartnell's insistence, though Glover makes no mention of this being a factor. Though perhaps the real issue is that the Doctor and companions spend many stretches of the story being superfluous to requirements, effectively guests in their own series. It's possibly the star of the show who fares worse, Hartnell acting as a backdrop to the acting chemistry of two excellent guest stars.