In 1973, Sam finds he's suddenly just a DI, and he has to report to the DCI of CID, Gene Hunt (Philip Glenister), a forthright and intuitive officer with whom he clashes. Both Season One and Season Two of the programme are available online from Amazon on DVD. A BluRay Release of both is also available, though contains only an upscale of the DVD content rather than being a "true" BluRay, so the quality is better, but not markedly so.

In the meantime, please join me in a ranking of the worst to best of all 16 episodes...

Life On Mars is such a quality series that even its four worst episodes are average entertainment. Episode six is a fairly standard hostage story, wherein wannabe ex-soldier Reg Cole (Paul Copley) takes prisoners at a newspaper office. Copley is always good value, but there's not really much tension in such a traditional set up, particularly with somewhat corny lines like "the price you pay is death", and Sam and Gene overpowering the gunman, then inexplicably deciding to run for it, leaving him to pick his gun back up.

Yet the real problem with such episodes is not small details, but the basic set up. All television is artifice, but a viewer instinctively knows when watching a story where one or more lead characters are held hostage/placed on trial, that they won't get shot/convicted, otherwise the series will end. While this applies to all elements of drama, it's particularly artificial in these set ups, whereby the entire working of the episode revolves around something you're intuititively aware will have no real consequences.

Continuity between episodes is generally strong on Life On Mars, especially considering the series is the work of seven separate writers. However, there's a slight shift in Gene's attitude to the press here, which indicates the three creators of the programme had different ideas about his character on some level. Matthew Graham and Ashley Pharoah (working together on the only episode with more than one writer) have him tell a reporter "I'd listen to the snot in my hanky before I'd listen to you" and derides the industry as "tomorrow's chip paper", whereas the previous episode had the third series creator, Tony Jordan, make Gene naively in thrall of the tabloid press, insisting that if something was "in black and white" it was undeniable. However, the opener of season two, written by Graham, has him deride the press as "bloody parasites", suggesting he'd resolved any sense of conflict within himself.

Co-creator Ashley Pharoah's sole script for the second season, this episode ups the comedy inherent in the format and takes Gene and Sam into the world of swingers parties in one of the least essential episodes. The plot is arguably the most contrived the series ever did, with a key witness to a murder case just happening to be thrown out of a car next to Sam when he's walking home, and him dreaming of his previously-unmentioned aunty the exact same episode he meets her in the past. This said, there's extra effort given to the normally thoughtful direction, with tracking and aerial shots implemented right from the start, and some of the situations are amusing, despite the show lowering itself to a couple of fart jokes.

There is always a danger with a comedy drama like Life On Mars that it will take the humour too far and undermine the more serious, psychological concepts underpinning it, in what is already a fairly "out there" concept. While Marshall Lancaster always give a fine acting performance as Chris, it's very much a "comedy character", who it's hard to imagine would realistically be employed by the CID, even one as ramshackle as Gene Hunt's 1973 troupe. Gene follows the same path in this episode, milking the laughs for all they're worth, though the revelation that he was sodomised as part of the swingers party is pretty amusing.

The one episode of the series that stands out awkwardly when rewatched as a whole. This article aims to be as spoiler-free as possible when reviewing the series, but one thing the ambiguous final episode alludes to is that the 1970s setting is not purely an artificial construct in Sam's mind. Such enticing ambiguity is further diluted by the sequel series, Ashes To Ashes, which takes away the mystery and gives solid confirmation of exactly where "1973" is.

However, this instalment has Sam, under medication in the future, hallucinating, and, in one memorable postmodern moment, able to see the other characters on a TV screen as reality begins to break down around him. More than this, the script aims to get around the narrative limitations of scenes only featuring Sam by having him able to see the flashback perspective of others when they touch him. While this does contain a reasonable Rashomon style change of perspective when Annie and Gene recount the same tale from differing points of view, it doesn't actually make any sense within the logic of the programme, unless the 1973 location is purely a figment of Sam's imagination. Such things were intriguing on the show's first airing, where viewers were left to wonder about the reality of the series, but ultimately contradict what we later learn on repeat viewings.

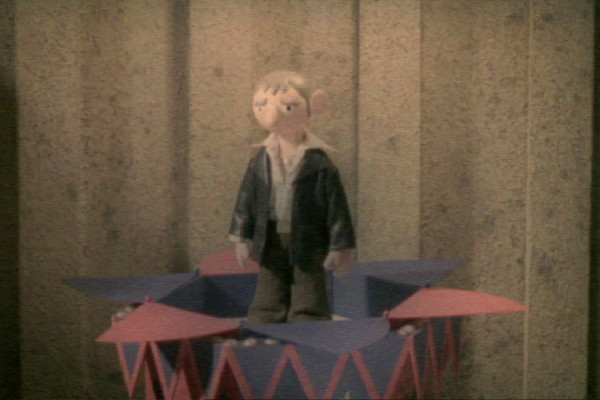

Also of note is the increase in slight silliness with Sam's interactions with 1970s characters. Before this, his experience with the Open University presenter and the test card girl had been quite sinister, but here he imagines himself and Gene as Camberwick Green characters. This element of "too far" fun would be expanded upon further in Ashes To Ashes, where new lead Keeley Hawes would imagine conversations with Zippy and George from Rainbow.

Co-Creator Tony Jordan's sole script for the programme, he was most famous for being the lead writer on Eastenders, a soap not exactly known for subtlety and implied subtext. So it is that this story about football violence has two young friends at its heart – one a City fan, the other United – who come to blows.

Life On Mars is a funny programme, but Jordan's overt comedy threatens to undermine the drama at times. It's scarcely believable that comic relief cop Chris would be able to get a job on the force as he's so dunderheaded, and the case – resting on the enormous contrivance that WPC Annie (Liz White) would talk about aftershave – is too rooted in artifice.

Sam's role within the 1970s is to comment from a modern perspective, and how things have improved since. This fifth episode features the most excruciating writing in the series as the final ten minutes grind to a halt so Sam can deliver a sermonising speech on the evils of hooliganism, and how it will lead to Hillsborough. While well-meaning, it's unnaturalistic, pious dialogue that leaks with the author's voice rather than anything the characters would actually say… all traits that are symptomatic of the worst excesses of Eastenders. All three creators of the programme had worked on the soap as writers, but Jordan was the one with the biggest grounding in the series.

The best part of the episode comes at the end, with Sam seeing himself as a small child, and a song that is, for once, not contemporaneous with the era in which it is set, with Nina Simone's 1967 track "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free". Lastly, Sam name-checks Doctor Who in this episode. Famously, co-creator Matthew Graham had asked his young daughter to suggest a surname for the character, not realising that she'd chosen it after Rose Tyler from the 2005 series. The new version of Doctor Who went on to feature John Simm, of course, shamelessly hamming it up as the Master from 2007.

For the writing of season two, then creators Matthew Graham and Ashley Pharoah wrote half the episodes between them, and brought back Chris Chibnall for another episode. The remaining three episodes were given to three new writers: Julie Rutterford (eleven), Mark Greig (fifteen) and, with this episode, Guy Jenkin. Jenkin is arguably the most famous writer on the series, most notably for his collaborations with Andy Hamilton on such series as Drop The Dead Donkey, Outnumbered and Kit Curran.

Despite his background being mainly in comedy, Jenkin delivers a very serious, edgy script for the programme. Featuring Ugandan Asian refugees and heroin dealing, the episode features six usages of the racial epithet "P***". Perhaps to offset what could be regarded as a very controversial subject matter, this is the first and only time we get to remeet Sam's 2006 girlfriend from the first episode, Maya (Archie Panjabi). Life On Mars was a very left-leaning show, which, while arguably commendable, depending on point of view, can occasionally make the programme and its lead, particularly during the more issue-based season two, seem a little preachy. In effect it can be reminiscent of another well-meaning but overearnest time-travel show, Quantum Leap, which would also see another Sam, as with episode ten, tell black people about the need for equality.

Despite the seriousness throughout most of the runtime, Jenkin's wit is still very much in evidence, with amusing lines like: "There's a viscous yellow liquid in his ear." "No, that's the drip from my fried egg butty, love." However, what causes a generally strong episode to rate so low in the ranking is the revelation that a suspect Sam is investigating turns out to be Maya's mother, a murder victim her dad. It's a contrivance too far in a plot that's already heavily dense, and does cause events to feel a little too muddled.

Modern TV isn't generally held in that high a regard here at The Anorak Zone, so Life On Mars is a rare exception. While it's a TV series that often acts like a Stuart Maconie list show recall of the 70s and features Philip Glenister as an analogue cum parody of Jack Regan, it's also surprisingly heartfelt and sincere. Occasionally the attempts at humour get a little too silly – as with the hospital brawl here – but John Simm gives a committed performance, and Glenister is able to add depths to what is, to a point, a two-dimensional caricature. Despite accusations of homaging 70s cop shows, particularly The Sweeney, Glenister states that it wasn't the exact intention, and that "if anything, I based him more on kind of a football manager. Someone like Brian Clough in the 70s."

That the supporting cast aren't always that finely sketched is part of the appeal of the series, of course – it forces the viewer to guess whether or not what we're seeing is real, or whether it's a delusion of a comatose Sam in the present. This episode follows a fairly routine case, but throughout Sam hears the sounds of doctors, and experiences lights switching off around him. This is also the first episode where he has a dream about the girl on the old 1970s test card come to life, with sinister overtones.

A sequel series featuring Keeley Hawes in place of Simm was broadcast from 2008-2010. Called Ashes To Ashes (or, if you're of a cruel state of mind, "Cash In To Cash In"), the series achieved decent viewing figures on a par with that of Life On Mars*, although critically it received mixed reviews. Although not every episode of the follow-up was seen here at the Zone, it shaved off many of the more ambiguous and enticing elements of the original programme by giving answers to the entire set up, including Sam's fate and the true nature of Gene. By effectively removing the "are they mad or back in time?" elements (which were still present, but now given more of a rigid explanation) it took away a lot of the element of surprise that made Life On Mars so great.

The second season DVD boxset of Life On Mars features Graham and Pharoah repeatedly saying they didn't want to milk the format or weaken the quality of the series by dragging it out too long, which it makes it doubly disappointing that they went that route.

* Life On Mars averaged 6.51 million viewers per episode, which was slightly less than the first two seasons of Ashes To Ashes, which averaged 6.55 million, aided by a high "opening night" viewing figure of 8.04m for the first episode. However, viewers began to drift away slightly during the third and final season, giving Ashes To Ashes an overall average of 6.41m per episode.

Rebecca Atkinson (Karen from Shameless) gets a role in this episode, along with one of her Shameless co-stars, Warren Donnelly. Fans of the Shameless cast are also treated to a prominent role by Anthony Flanagan in the fifth episode.

Adding to the guest cast here is Lee Ross, making the first of three appearances (the third in Ashes To Ashes) as DCI Litton. Ross has appeared in movies, including Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and The English Patient. However, to a certain generation he'll always be known as Kenny from Press Gang, or, for those even older, his first role on TV in Dodger, Bonzo and the Rest. Ross is always good fun, but he looks too young for the part even in his mid-30s, and he is sending it up quite a bit. Thankfully the character doesn't reappear in Life On Mars' second season, allowing it to be a little more serious in general.

As the third episode, then this instalment tones down the questions regarding Sam's sanity and reality, but scores by having a tighter plot than the first two. The openers acted as fairly bog standard murder enquiries that used contrivance to resolve the cases, just window dressing to introduce the characters and set up. This investigation into what appears to be a factory slaying involves genuine detective work and a fairly clever resolution, placing the reality of the 1970s over the central mystery. Although the mysteries are what keep the series watchable, it's important that the cases are also well developed, and a perfect balance between the two is the ideal.

The first episode, and the one with the highest ratings, the "first night" advertising of the show encouraging 7.46 million people to tune in. Although figures inevitably dropped thereafter, the show maintained a solid following throughout the first season. Created by Tony Jordan, Ashley Pharoah and Matthew Graham, the first season was largely written by Graham, with him delivering scripts for half the eight episodes, and co-writing another with Pharoah. He went on to write three more for season two, including the final episode.

This introductory story by Graham is generally a strong one. The resolution to the first case is more than a little contrived, and some of the dialogue to indicate the reliance on technology in the present day is a little on the nose ("Look around you. What use are feelings in this room?") but for a first episode, it does a good job at setting up the basic premise.

Both DVD boxsets of Life On Mars were impressive releases, coming with lots of extras, including behind-the-scenes features, yet only season one came with commentaries. DVD commentaries are more often than not inessential chats rather than must-hear events, though they're a nice addition in principle. The commentaries for every episode of season one lean more towards the latter, though are pleasant enough listens. If you want to hear which extra was John Simm's real-life dad, Tony Jordan say he didn’t know what the series was about, or hear Philip Glenister jokingly refer to the internet as a "breeding ground for perverts", then they're diverting enough.

In terms of actual content, then this first episode is the one to really listen to, with genuine insights, including subplots that were removed, ideas behind the series and which scenes were filmed weeks apart. Featuring on the eight commentaries in various combinations are the producer, four directors, all three creators, writer Chris Chibnall and the actors behind Sam, Gene, Ray and Chris.