The sole episode of Julie Rutterford, who had already written for John Simm with three episodes of The Lakes. While the relationship between Sam and Ray had begun to warm slightly over the preceding episodes, here it's even worse than ever, as Ray gets hit by an explosion which Sam insists couldn't possibly happen. Sam's suggestion that Ray takes counselling is met with one of the most memorable of Gene's lines: "he's a police officer, not a fairy."

The episode ends with a reference to a chunky KitKat, which Annie – unaware of the new bar introduced in 1998 – takes as an insulting reference to her weight. While by no means fat, actress Liz White was, with all due respect, probably a dress size above what most TV shows of the time were promoting as the "ideal woman". White's casting is something for which Life On Mars should be commended, where the programme refused to promote a misleading and potentially harmful concept of what a desirable woman should look like.

Broadcast slightly later in the year, poor scheduling and sporting fixtures had an impact on the second season's ratings, and they were initially down, though recovered in time for the finale, which got back up to 7.44m. This episode, about a suspected IRA attack, was the lowest the ratings ever dropped, just 5.23 million people tuning in. While this sounds quite low, particularly for those of us who grew up with the TV ratings of the 70s and 80s, Life On Mars was still considered a ratings success for the BBC, frequently winning its particular timeslot, and being the 33rd most-watched programme in the UK that week.

While competition from ITV was strong during the time Life On Mars was on air, frequently having more higher-rated programmes than the BBC, for its home channel Life On Mars was consistently in the most-watched BBC shows, only twice falling out (with this instalment and episode twelve) of BBC1's top ten. Speaking of trivia, then while Life On Mars generally came in around the same length, this was the shortest episode at 57'17 minutes. The longest, lasting just a couple of seconds longer than an hour, was the series finale, the running time of which was bolstered by recaps at the start.

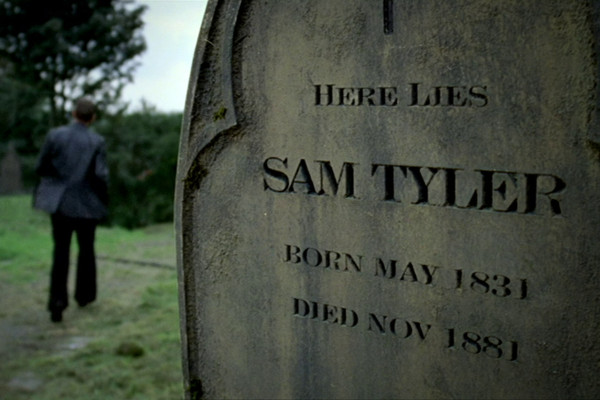

Lastly, while the opening credits still list 1973 as the year where Sam awakes, there's a feeling that time must have passed between seasons as it aired a year later. This appears to be confirmed in this episode, where Gene makes a reference to the programme The Wheeltappers and Shunters Social Club, which began airing in 1974. Contradicting this is a demand letter that Sam finds in an office, dated January 1973, and Annie's remark in the following episode "don't worry, it'll be 1974 soon." However, such contradictions do help the suggestions that much of the experience is in Sam's mind.

To this point in the series, Life On Mars had mainly tackled institutionalised sexism and, to an extent, homophobia. However, this is the first episode to challenge the attitude towards race in the 1970s, giving Sam a unique perspective. When DC Glen Fletcher (Ray Emmet Brown) joins the team on a temporary assignment, he has to make a series of self-mocking racial taunts in order to get onside with the team, particularly the bigoted attitude of Ray. Of the 1970s force, only Annie, newly drafted in as part of the team, looks appalled.

What's difficult to recall now, particularly for those not alive during the era, is that such ingrained casual racism was part of the make-up of Britain, certainly its television media, and that even left-wing satirical shows like The Goodies were using racial epithets, and not always, by their own admission, for pure motives. In the 1973 in which this episode is set, then The Black And White Minstrel Show would have been in the fifteenth of a twenty-year run. A look back at many of the programmes of the day, as via Channel 4's skewed but worthwhile 2014 documentary It Was Alright In The 1970s show that even seemingly innocuous programmes like Film '76 had Barry Norman saying "n*****".

This is not to suggest, of course, that everyone would have been involved in such activities, but the 1970s really were, as Sam Tyler has it, "a different planet", and that now-vilified comedians like Jim Davidson had acts that were regarded as mainstream entertainment. For some direct perspective on the era in which Life On Mars is set, then in 1973 Love Thy Neighbour was one of the ten most-watched programmes on TV... in 1974 it was the second. There is a case to be made that Love Thy Neighbour was, in a very broad way, trying to promote racial harmony, but that's perhaps a very long debate for another time. As Roy Hudd wisely says in the documentary, "You cannot airbrush history."

Ironically, Brown's own real-life career echoes the lack of choices for black people in industry to this day: he admitted in an interview with The Guardian that he trained as a barrister after a series of bit parts playing crooks and thieves. Three years before Life On Mars he'd had his first starring role in the series Outlaws, and he again worked with John Simm in 2014's Prey, yet his acting roles are still sparse for a man of his talent.

Such matters also highlight one of the fundamental issues that some viewers may have with Life On Mars: many of the cast and crew have said, possibly with tongue in cheek, that the 1970s setting was a way to get un-PC dialogue past the censors, with Simm even describing Sam as "a bit of a dick". Such things are fine as Sam acts as a moral compass to challenge it, but as he begins to gradually accept his other life throughout the second season, it does unfortunately give the series the perhaps unintended subtext that things were "better" back in the old days. This isn't helped by the fact that the first episode shows Sam splitting up with his Asian girlfriend Maya and he finds himself falling for Annie throughout the run. However, such things are probably unintentional byproducts of a series that tries to do many things throughout its run.

Lastly, a note of trivia: Life On Mars, while well made, does occasionally suffer from poor intershot continuity, and the moment 30'18m in where Sam bows his head at frustration at being interrupted by Gene – to instantly cut to a forward shot where his head is upright – might rank among the worst.

The penultimate episode of Life On Mars was written by Mark Greig, a writer with a background on police procedurals like Taggart, Rebus, The Bill and The Inspector Lynley Mysteries. A decent fit for the show, he went on to write three episodes of Ashes To Ashes.

As discussed with episodes about sieges and trials, then this one is based around a very familiar trope of the genre: the lead character is charged with a murder he claims he did not commit, but all the evidence suggests otherwise, cueing a race against time to prove his innocence. In another series this would be dramatically inert, but in Life On Mars not only have we been led to believe that Gene may be capable of such actions, but the backdrop of Sam's psychodrama adds extra flavour to what should on paper be a fairly pedestrian plot.

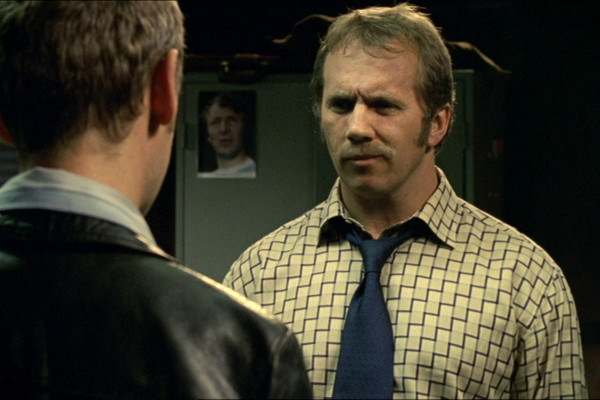

Most importantly, there's Ralph Brown. Introduced as Sam's supervisor from "Hyde Division", there's hints that Sam is on a covert mission that he's unaware of, and that Brown's Frank Morgan is there to provide the way back to 2006, a subplot picked up in the final episode. The name of the character was also the name of the actor who played the Wizard in The Wizard of Oz, one of many tantalising references throughout the programme to the 1939 film, as well as other media, such as both Alice books.

Lastly, Gene dressing as Tufty the Squirrel is one of the more overt humour moments the series indulges in, but for such a serious episode it works well. An episode based around the boxing underworld, sharp-eyed boxing fans might notice non-speaking extra roles for Matthews Macklin and Hatton, as well as trainer Billy Graham.

Co-Creator Ashley Pharoah wrote one script for each of Life On Mars' two seasons (as well as co-writing episode six with Matthew Graham) and this was his contribution to season one. It's a shame he didn't contribute more, as this fourth episode introduces more emotional resonance, with Sam meeting his mother in the 1970s and his relationship with Gene growing deeper.

The music to Life On Mars is a crucial element of the programme, both it and its sequel series being, of course, named after 70s and 80s tracks by David Bowie. No one could have guessed that, ten years after the series began, the singer would no longer be with us, his death occurring just the day after the tenth anniversary screening of the first episode, a sad loss. Investigating a crooked club owner, the music is prominent here, with Bowie's "Gene Jenie" (a name which Gene uses to refer to himself) being played over events, as well as other tracks by Jethro Tull, Hawkwind and The Sweet. Sadly, some of the songs used in the series – including four tracks by Deep Purple – weren't available on the DVD releases due to rights issues, and songs were substituted in their place. Of this particular episode, then The Rolling Stones' "Wild Horses" was replaced by Frankie Miller's ironically-titled "I Can't Change It".

Life On Mars was released in the UK on DVD boxsets, with seven of its eight discs getting a 12 certificate. The BBFC has no record on its site of why the fourth disc, containing episodes seven and eight, received a 15 certificate. What's surprising though – at the risk of sounding like the Mary Whitehouse namechecked in this episode – is not that two episodes should be rated 15, but why the rest were released with a 12 certificate. Life On Mars was a post-watershed series that contained adult themes, and this particular episode features a brief sex scene with a topless girl who later appears with her throat slit, and the nightclub owner performing oral sex. That the BBFC felt that this was acceptable viewing for someone aged 12 shows how loose standards have got since they days when Emu's Pink Windmill was released with an 18 certificate*.

* This didn't really happen.

On a personal note, then this was the first episode of Life On Mars I ever saw, purely by chance on channel hopping. Catching it halfway through, I became engrossed in a series I'd consciously avoided as the BBC trailers made it look so flippant and silly. The series was originally envisaged, years earlier, as a comedy format, and the advertising for the series made it look very much like the sitcom starring Neil Morrissey it was touted as being when first pitched to the BBC. Thankfully, not only is Life On Mars nothing like that, but the last two episodes of season one get darker than the ones they followed, making it actually an ideal jumping-on point for someone cynical about what the show might be.

Chris Chibnall is the only scriptwriter for the first season who wasn't one of the creators. The man behind Broadchurch, he was also headwriter on Torchwood and has been confirmed as the new showrunner of Doctor Who, starting in 2018. Although Chibnall's work on some of these programmes is open to question (Cyberwoman and Dinosaurs on a Spaceship perhaps not qualifying as "high art"), his work on Life On Mars is fine, and this is a very dramatic episode, with Sam investigating his own department for corruption.

There's a sense of things returning to a vague status quo at the end, which makes for nice dramatic irony (Sam realising that the rot comes from above, and he's powerless to change it) but Chibnall was critical of his own writing at restoring the relationship between Sam and Annie. While it's mildly jarring that they have to become friends again in time for episode eight, on the commentary the writer notes "I don't think I got this last scene right [...] the shift into the smile at the end, it's not quite as delicate as it should be."

Lastly, the DVD box set contains a six minute outtake reel... the moment where Ray (Dean Andrews) and Chris reference Deliverance causes John Simm to break into laughter and blow two separate takes. All concerned clearly thought it was so funny that a variation on the joke got reprised for Chibnall's other episode, episode ten, where Ray and Chris show Simm what it looks like to mount a sheep.

Investigating a case involving gangland executions and illegal pornography, Sam finds his own father right at the centre. With his father having disappeared in 1973, Sam believes he can change the past and bring his family back together... but finds that his dad is not the man he thought he was in this engrossing climax to the first season.

Although the BBFC site has no information confirming why the disc containing this episode and episode seven was the only one with a 15 certificate, it's almost certainly due to shots of a simulated black and white soft porn film, which CID confiscate and then watch in the office. Episode seven does feature an autopsy that goes into slightly more graphic detail than most, but which was unlikely to have impacted the certificate, any more than Simm's multiple uses of the F-word in the disc's outtakes reel.

The second season begins with perhaps the most successful marriage of the two timelines. Sam and Annie almost share a kiss, but it's interrupted just at the crucial moment. Such things are common in drama, but this is almost certainly the first drama that has a kiss interrupted because one of the couple is being murdered in the future as it takes place. Tortured in his hospital bed by villain Tony Crane, Sam's existence in the 1970s threatens to be wiped out, as his prone body is being threatened with murder. Sam knows he has to stop Crane in the past in order to save himself, but no one will believe him, and the Crane of 1973 appears to be a spotless businessman.

Crane is played by Marc Warren, who had appeared in productions with Simm before – the 1995 film Boston Kickout and the 2003 mini-series State Of Play. State Of Play also featured Glenister, making this the second time all three had appeared together - however, their most notable collaboration was with the TV series Mad Dogs (2011-2013), which featured the trio alongside Max Beesley in a black comedy gangster thriller.

As a starting point for a fresh season, it's a spectacular start, with the macabre use of the Morecambe and Wise theme being whistled as Sam is being put to death. What makes it especially horrifying is that, like Sam, we never see the things being carried out on him in the present, only their effects in the 1970s timeline. This also marks the first time that the other CID officers have been let in on Sam's secret that he believes he has travelled in time – something previously only shared with Annie.

If a TV series is to be judged on its last episode, then Life On Mars was first rate. Featuring a multi-layered resolution that provided a tragic happy ending, it also had enough ambiguity and meta-referencing of form – the final shot is the test card girl switching off the screen for the viewers at home – to make it a true classic. To discuss wider details of the episode would be to give away spoilers, but the programme finally consolidates its urban western fixations as well as giving more Shameless actors a payday.

Probably the only element that's dated Life On Mars since it aired occurs with the start of this episode, where Jimmy Savile's voice (probably an impressionist, though it's uncredited) comes out of the radio. Of course, even in the 2006 that Sam Tyler comes from, Savile was still a much-regarded media personality, something that's hard to consider just nine years after this particular episode was broadcast.

If there is a change in style in the decade that followed, it's that TV has become even more fast-paced and choppy, even more enthralled by never letting scenes breathe. Life On Mars is never afraid to let scenes run, and allow audiences to sink into the characters and situations. This is especially notable here, where over 12 minutes of the middle of the episode is a two-hander between just two characters, albeit over three separate locations. Such things are often a lost art in a lot of today's TV, and it's such an adherence to the dramatic functions of yesteryear that make Life On Mars a modern classic.