Television movies being poor cousins to their cinematic counterparts is now possibly a thing of the past. While they'll never perhaps have quite the same budget, broadcasters like HBO have improved the standing of both regular television and feature-length productions on the small screen over the last few years. Yet for most of its history, TV movies have more often been misses than hits. A true classic on a TV scale like Cathy Come Home was rare... a film that could have (and eventually did) exist in cinemas like Duel was even rarer.

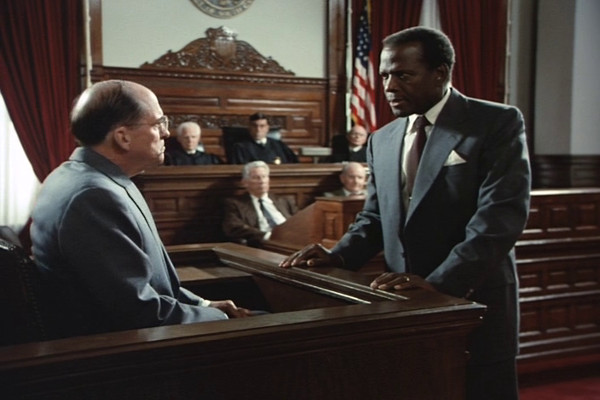

Separate But Equal is the first and best of Sidney Poitier's television movies as it makes no real attempt to compete. Here there's no desperate scrambling for scale; instead the film plays out as a relatively small scale courtroom drama. Although punctuated by some harrowing scenes, the teleplay is enlightening without being unduly engrossing, and contains one of Poitier's most mannered performances.

Yet it's objectively the best of his TV ventures, a work that exists more as an educational look back at history rather than something that exists purely as an entertainment. As his first TV movie before returning to cinema screens with Sneakers, it feels less like a late career decline and more just a story he really wanted to tell, but in full acknowledgement that it wouldn't sell as a popcorn flick.

As the film that marked his initial retirement from acting, then this isn't a bad film for Sidney Poitier to bow out on. He even gets to teach a class of unruly kids and educate them on discipline and self-respect, almost like it was a decade earlier. Although this is regarded as the final part of the Cosby-Poitier comedy trilogy, A Piece of the Action is more like a comedy thriller than an overt humour vehicle. Most of the laughs arise naturally out of the piece, rather than Poitier's friends coming on and doing "turns" as was the case in Uptown Saturday Night. The film has a lot to say on the human condition, and, while heavy-handed in the way it says it, does so well.

After this, Poitier directed three comedies before being tempted out of acting retirement in 1988 to film Shoot To Kill/Little Nikita. He returned to directing, and his last collaboration with Cosby, with lacklustre 1990 comedy Ghost Dad. The film was critically panned, and Poitier never directed again.

A feature film about the basketball team The Harlem Globetrotters, who had released a self-titled movie in 1951. The first film had seen Globetrotter Inman Jackson as himself, but in this follow-up movie he's portrayed by Sidney Poitier, with Dane Clark playing the manager, Abe Saperstein. It's also the first credited appearance in a Poitier movie for Ruby Dee, after an uncredited role in No Way Out. His most frequent co-star, she also made appearances in Edge of the City, Virgin Island, A Raisin in the Sun and Buck and the Preacher.

The Globetrotters aren't professional actors, and there's a certain primitive quality to the film, all of which only adds to the charm. Although ostensibly a sports movie, there's a romance that acts as the main plot throughout most of the picture, and when the basketball element does take over, right at the end, it's presented in an engrossing manner that brings out the drama of the final game.

The second sequel to In The Heat of the Night, today The Organization has the ignominy of being a film that most people haven't heard of. In The Heat of the Night novelist John Ball had written two sequels of his own in print, and would go on to complete seven Virgil Tibbs novels, along with four short stories based around the character. However, the films took their own divergent route, and this original plot has a gangland organisation dealing in heroin, and an undercover outfit attempting to stop them, with Tibbs trapped in the middle. The undercover gang vary in quality – Raul Julia went on to greater success, but Lani Miyazaki gives an astonishingly poor performance.

Gil Mellé takes over the musical score, and Don Medford the direction, while James R. Webb (co-writer of the first sequel, "They Call Me MISTER Tibbs!") completes the screenplay alone. As with Tibbs, there is sometimes an unintentional "70s TV movie" feel to it all, with some sloppy editing and continuity. Look out, for example, for 40 minutes in, where Tibbs lowers his gun from behind – before cutting to a front shot where he still has it in the air. Or check out the hilariously bad jump cut near the end of the film, where a man is "run over" and "knocked over the bonnet of a car".

Somewhat dour and nowhere near as much fun as the first sequel (intentionally or otherwise), The Organization marks the first real sign that the hunger is starting to fade for Sidney. Still capable of burning up the screen in Tibbs, here there's signs that he's starting to look a little bored, and his later, mellower performances were soon to follow.

At the peak of his success, Poitier was openly criticised for "selling out", his portrayal of the "perfect black man" helping white people with their problems seen as a form of "Tomism". Perhaps most famously of all, the playwright Clifford Mason penned an article in 1967 entitled "Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?", slating him as a "showcase n***er".

Although Poitier states that he never took criticism to heart, friends state that it affected him deeply, and it's notable that his work, whether by coincidence or not, became more orientated around black concerns thereafter. The Lost Man has him as a leader of a black militant gang, his acting skill managing to make some headway into this somewhat unlikely role. Poitier does get some considered lines of dialogue in the picture, though the more it turns into a straight thriller, the less vibrant the script. His co-star is Joanna Shimkus, who became Poitier's second wife seven years later.

An interesting take on Sidney Poitier can be gleaned from reading the 2011 autobiography of his friend and sometime rival Harry Belafonte. Belafonte is candid about Poitier's mistakes and limitations when he feels it necessary, and he states that as a director, everyone knew that Poitier wasn't Martin Scorsese, including Poitier himself.

Buck and the Preacher, co-starring Belafonte, was Sidney's first directing job after the original director Joseph Sargent was fired due to creative differences. (Sargent would later go on to direct Poitier in the TV movie Mandela and de Klerk). Poitier directed a further four of his own films before retiring from acting in 1977: A Warm December, Uptown Saturday Night, Let's Do It Again and A Piece of the Action.

Buck and the Preacher isn't a particularly outstanding work, but does provide audiences with a rare racial perspective in westerns, in that the native Americans troubled by white cowboys are here presented as on different terms with black people who don't share the same history of conflict. Although Duel At Diablo attempted to tell a Western through a libertarian perspective, and is the better film, it still portrayed native Americans as "savage Injuns", something that Buck and the Preacher does not fall into. This is a Western produced, directed and starring black professionals, only the writing credits falling to a white man. To all intents and purposes this is black cinema, rather than white cinema that happens to star a black man, a description that applies to the majority of Poitier's work.

Poitier's direction is occasionally inspired, but always serviceable throughout, a man who was just interested in getting movies made without undue artistic flair. He wasn't in the same league as many of the men that had guided him before a lens, no Stanley Kramer, or no Norman Jewison. But then he was capable of delivering a diverting package that was easy for anyone to enjoy, and no one ever rated Stir Crazy on its mise-en-scène.

Poitier and Paul Newman star as couple of Paris jazz musicians, haunted by their own fears and insecurities, getting involved with two visitors to Paris in love affairs that ultimately fail. Poitier himself suggested that the film would have been more memorable if the two couples in the film were swapped around, giving them both a mixed-race relationship, and described the project as "one dimensional", though it's possible to view the film as a romance of a different kind as the two headlining stars dump the girls to be with each other. Ultimately, despite containing some darker themes, such as the race question and drug addiction, it's a servicable film rather than a great one. The tagline for the film promised "A love-spectacular so exciting you feel it's personally happening to you", whereas the reality is, you'll probably just think it's happening to Newman and Poitier, who both had more significant and historically lasting films that same year. (The Hustler/A Raisin In the Sun).

Probably more interesting than anything happening on screen is what was happening behind it. Sidney, his first marriage breaking down, met Diahann Carroll while working on Porgy and Bess, and the two began to fall in love despite all attempts to stop. Although their romance had cooled with time apart, working together once more on Paris Blues caused them to be closer than ever, and plan to get married. Sidney divorced his wife, but Carroll, with a new baby by her husband, changed her mind and ended the affair in 1966.

One of the few entries to truly fall under this site's SF/fantasy remit, whereby Poitier appears as "Brother John", who talks of overseeing the final judgement on Earth. Although his brother's name is Gabriel, and there's dialogue that points at him being the second coming of Christ, it's left suitably ambiguous as to John's true nature.

Listed as "science fiction" on the Internet Movie Database, the climatic conversation between John and Will Geer's Doc Thomas sees the elderly doctor speculate that John may just be a "paranoid schizophrenic" and that he may be sharing his delusion. Although John concludes "that's possible", he also discusses the nature of mankind. After experiencing bigotry and hatred in a small town throughout the film, he concludes that there is little hope left for the world.

Poitier himself cleared up some of the ambiguous nature of the film, stating that John was "an observer from another world", and made the film with his own newly-formed company, E & R Productions. Sadly, despite the care of everyone involved in the making of it, it wasn't a hit, and with the emergence of popular Blaxploitation movies, Poitier's career continued to stall until 1975.

Above average yet not quite classic western featuring James Garner and a memorable score by Neal Hefti. Some of the casting choices are left-field, such as the very English Bill Travers as the leader of the US Army, though it's rewardingly visceral for the time, with some very well-staged stunt work, particularly involving horses.

There's a greater swagger about Poitier in his early period, and his cigar-chomping cowboy Toller is one of his most bold, arrogant characters. This said, Toller, for all his bravado, does accept his lot as a man riding first into "Injun" territory... the idea being that, should he be killed, the US army behind him will know the area is dangerous. It's one of the few times that Sidney essays a character who wilfully accepts a submissive role in his life, despite the fact that Toller is, on the surface, one of the most confident.

As Toller is the most iconic of Sidney's characters for smoking, then it may come as a surprise just how often he smoked on screen throughout the early stage of his career. This was the eighth of his films to this point to see him puffing away on cigars and cigarettes*, even Cry, The Beloved Country where he plays a priest. The actor had smoked since he was 17, and gave up some time after filming Porgy and Bess, though can still be seen smoking on screen into the 1970s. His addiction to smoking and his difficulties at quitting the habit are detailed widely in his third autobiography, Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My Great-Granddaughter.

* Technically he doesn't smoke in 1961's Paris Blues, where he's about to light a cigarette but is interrupted and blows the match out before throwing the cigarette away. But the intent, as well as the implication that the character does it, was there. And, for completeness' sake, then he sits in front of a smoking cigarette in an ashtray during A Raisin In The Sun but it's not explicit as to whether it's his cigarette or one of the two friends that are with him... even though he does later play with a match.