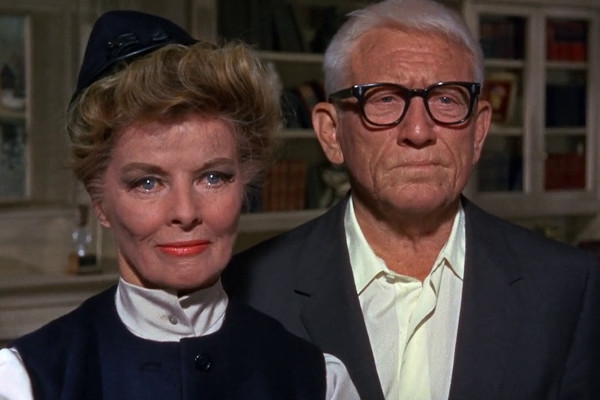

Almost inarguably Poitier's most famous film, where his desire for an interracial marriage is met with doubts by the fiancé's liberal parents. Thankfully, while prejudice still very much exists, the concept of an interracial marriage and mixed race children is no longer an alien concept that you could build an entire film around, even in the upper classes. Indeed, Poitier had a real-life interracial marriage less than ten years later, taking vows with Joanna Shimkus in 1976.

Watched today it's a film now so of its time that Katherine Hepburn can describe Poitier's mother as "a good one" without it seeming like racial patronage. A film where John's enlightened liberal fiancé alternately refers to him as "coloured" and "a negro". Sometimes overwritten and often feeling studio-bound, it's nevertheless one of the most essential works in Poitier's canon.

Ruminations on whether their children would ever be President now date the film (Barrack Obama was a six-year-old boy when it was released) yet it excels with the empathic performances of the stars. Spencer Tracy, gravely ill, would be dead less than three weeks after filming, and the tears in Hepburn's eyes are real. The husband and wife team give standout performances, though were not able to witness Sidney's own... he was so nervous in their presence due to his relative lack of experience that he performed his big speech without them present. The film achieved Poitier's biggest box office, with ticket sales that would register just shy of $480 million when adjusted for inflation today.

As well as the fifty-one film roles in this article, Poitier had also appeared in four short television plays in the 1950s. The last of those roles aired on 2nd October 1955 as part of "The Philco Television Playhouse". Said play, "A Man Is Ten Feet Tall", was later rewritten and expanded into Edge of the City. Although director Robert Mulligan didn't get to shoot the film version (which fell to Martin Ritt of Paris Blues), writer Robert Alan Aurthur did the adaptation of his own work, and went on to write two further film screenplays for Poitier: For Love Of Ivy and The Lost Man.

The film went on only limited release due to what was then a controversial theme, depicting an interracial friendship. Poitier details one of his less restrained performances as the good-natured motormouth Tommy Tyler, boss and friend of John Cassavetes' troubled Axel Nordmann. Although the film frequently gets unfavourable comparisons with the earlier On The Waterfront, it's a solid film in its own right, with some unusual characterisations for the time, not least Nordman's true nature. With subtle hints that he was really homosexual, the Motion Picture Production Code advised "extremely careful handling" in the way it was depicted. It's possible to view the film without this added dynamic; yet watching it with the subtext in mind adds an extra layer to the narrative.

Many of Sidney Poitier's best movies are sentimental to the point of saccharine mawkishness and may not appeal to all – chief offenders being A Patch Of Blue, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, To Sir, With Love and this entry, which sees Homer Smith (Poitier) help a group of German nuns build a chapel. A charming picture, detractors demean the plot of Smith working for free for domineering white nuns, but he defies a man who calls him "boy", and works for the nuns out of open love.

His playful performance saw Poitier win a Best Actor Oscar, the first black actor to win such an award (although James Baskett and Hattie McDaniel had won honorary and supporting Oscars). Such an achievement perhaps throws unwanted attention on a slight yet endearing film, and also throws open to question why Poitier didn't win one for The Defiant Ones (for which he was nominated) or In The Heat of the Night (which he wasn't). The film also won the Oscar for Best Picture, and was only Ralph Nelson's second movie for cinemas. Thanked by Poitier in his Oscar speech, Nelson went on to direct the star again in Duel At Diablo and The Wilby Conspiracy and directed a 1979 TV sequel to this movie with Billy Dee Williams, Christmas Lilies of the Field. It's a film that doesn't really require one, as the understated, bittersweet ending and stellar chemistry between Poitier and Oscar-nominated Lilia Skala is what sells it.

Lastly, The film contains Sidney's most prominent "singing" performance outside of Porgy and Bess. He was required to mime to the voices of others multiple times throughout his career, including The Defiant Ones, A Patch Of Blue (badly), Band Of Angels (even worse) and Blackboard Jungle. The only real time that Sidney's own self-admitted tone deaf voice can be heard on film is when he tries to accompany Bill Cosby for a few notes in Let's Do It Again, or singing the wedding march tune in Virgin Island. Here, still in his mid-30s, he mimes to the voice of a man over 25 years older, and viewers are required a certain suspension of disbelief. The voice (which belonged to Jester Hairston, the butler from In The Heat of the Night) clearly sounds nothing like Poitier's own, though initiates a charming gospel spiritual, "Amen", written by the singer.

Nearly 55 years old, this film will now divide audiences, and I've seen critical reviews that slate its heavy-handed religious theme. Yet I truly believe it's possible to watch this film – a film named after a quote from the Bible chapters of Matthew and Luke, and which ends with a large "Amen" written on the screen – not as a religious film. Although the nuns believe in God, Smith helps them largely out of human kindness, and the final closing sequence – where the mother superior knows he's leaving, but refuses to acknowledge it – is a typically tear-inducing ending, where what remains is the connection between two people and all the things that go unsaid.

Unashamedly and nakedly earnest, To Sir, With Love's main intention is to induce tears in the eyes of the viewer. Although relatively short at 105 minutes long, the film is effective at capturing the passage of time, and allowing the viewer to feel they've experienced a journey with the characters; even if that journey isn't entirely realistic.

The film was one of three massive hits for Poitier in 1967/68, taking over $42 million in the US alone and being the eighth biggest film of the year in the States. (In his home market, then In The Heat of the Night was twelfth, and Guess Who's Coming To Dinner was third, only held back by The Graduate and The Jungle Book). Amazingly, the title song by Lulu was only released in the UK as a B-Side, and thus unable to match the success it had in the US, where it spent five weeks at No.1.

One of the most influential Sidney Poitier films of all, which made little-selling Bill Haley track "Rock Around The Clock" a No.1 hit, and caused multiple riots at cinema screenings. The birth of what was known as "rock and roll" was an evolutionary process, so much debate goes on as to what the first rock and roll record actually was. Certainly, some of the earliest suggested contenders (such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe's "Strange Things Happening Every Day") are more what would be considered boogie-woogie, but mark the development of music from straight jazz/gospel into a broader form.

Such events are a reminder that Poitier's career stretches so far back that modern rock music as we know it had yet to be invented when he first appeared on screen, an almost incalculable mindset to anyone born from the 60s on. As a personal note, then my favourite rock and roller was always Little Richard, and it's almost amusing today to imagine people trashing cinemas to the now-quaint Haley (In contrast, Richard's impassioned piano playing and banshee-like screaming still retain a level of unorthodox danger even today). The opening track is now very much an "easy listening" number, and became the original theme tune to cosy nostalgia sitcom Happy Days less than twenty years after it was released.

Yet while the soundtrack is tame in 2017, the film is not. It's obviously dated, as any film over sixty years old would be: the entire thing, even "exteriors", are shot in a studio, editing is sometimes sloppy, and the lighting is flat, not making the most of the possibilities of black and white filming. But there's an attempted rape within the first 25 minutes, naked cruelty, and a climactic, bloody knife fight that was cut from its original screening in the UK.

The most obvious film to compare this to is To Sir, With Love, with Glenn Ford in the role of earnest teacher and Poitier as a rebellious pupil, but the pupils here make the classroom of To Sir, With Love look like a kindergarten, and not just in the way there's hardly a single "teenage" pupil below the age of 25. Whereas the residents of the London school were not beyond redemption, here there's a genuinely brutal, oppressive edge, with violence erupting throughout the picture. To Sir, With Love is by some way the more likeable and charming film... but Blackboard Jungle scores higher due to its visceral power.

Time perhaps hasn't been overly kind to The Defiant Ones, where, now sixty years old, the plot can seem a little pedestrian, and the social commentary overlaboured. What doesn't help matters is that, while there's still a lot of work to be done to improve racial dynamics, the immediate distrust Poitier's skin colour incurs throughout is literally from another age.

While the film can seem like "issue first, story second", the chemistry between Poitier and Tony Curtis (who insisted, in the spirit of the movie, that Sidney received co-billing) is superb, and the ending is as perfect as ever. In many of his earlier film roles, Poitier wasn't quite the infallible gentleman he would later become, and here he's more of a three-dimensional character with a severe attitude against the world. Although in 2017 The Defiant Ones is more of an historical document than a mainstream movie, it still stands up as a rewarding work. And, if nothing else, it gives an overriding urge, whenever the phrase "bowling green" is heard in real life, to shout out the rejoinder "sewing machine!"

In compiling this ranking, it's sometimes been difficult to compare very different films to one another, from westerns to comedies to schmaltz to social commentary. At one stage The Defiant Ones wasn't even going to make the top ten. What gives it a very lofty top three placing is that, ultimately, it is the most iconic Sidney Poitier film of all time, and that final, bittersweet ending does play the film out with a possible lump in the throat of the audience.

While Sidney Poitier's work in breaking down racial barriers in cinema cannot be underestimated, it should also be acknowledged that there were those who came before him, and had to endure even more demeaning and restrictive conditions in the medium. Sidney was born on February 20th, 1927, by which time lauded black actors like Paul Robeson had already entered the profession.

A full and detailed discussion of black history in Hollywood would be too complex to go into in any great detail here, but covers such disparate elements as Lincoln Perry (the first millionaire black actor, who debatably reinforced negative stereotypes/exploited the system for satirical purposes), Hattie McDaniel (The first black Oscar winner for supporting actress, playing the racially questionable "Mammy" in Gone With The Wind), Robeson himself, and the concept of "blackface". Such issues are deeply complicated and speak of the attitudes of the times as much as they do the industry itself. As one last note, then the term "African-American" is often used in modern parlance, a term I've studiously avoided throughout this article whenever it's come up, as it's often misattributed to people it doesn't actually apply to, with Poitier himself having a background not in Africa, but in the West Indies.

Another actor of great historical importance is Canada Lee, a stage performer and political activist who had worked in the movies until blacklisted by Hollywood. The beautifully-named Cry, The Beloved Country was produced by a British firm, London Films, and shot in South Africa, thus getting around the politically-motivated blacklist. Lee had a heart attack while filming, and his health gradually deteriorated further, dying less than four months after the film's release.

Lee portrays a man in search of his son, helped by his friend Reverend Msimangu (Poitier), who discovers with him the effect that apartheid has had on his son in Johannesburg, leading to his son committing murder. It's an illustration of the length of Poitier's career that this, his second picture, can cover apartheid, and 44 years later he was portraying Mandela after the abolition of segregation.

A film of great beauty and sincere poignancy, it won the Bronze Berlin Bear at the second Berlin International Film Festival and is a showcase of Lee's tremendous screen presence, his haunted expression throughout deeply touching. However, while it deserves its lofty position in this ranking, it's neither an especially great showcase for Poitier (who, while fine, disappears for long stretches of the narrative and appears to have a different timbre of voice at the beginning and end of the picture) nor is it a dramatically vibrant work. Ponderous and contemplative, it may lack pace for modern audiences, though if the film is worked at, it offers rich rewards.

The aftermath of the film saw Poitier spend much of the early 50s pursued by authorities, who insisted he sign a Loyalty Oath for his association with men like Lee and Paul Robeson. His refusal and his feelings about their ideals can be further explored in his second autobiography, The Measure of a Man.

There's an off-quoted myth that the In The Heat of the Night scene where Poitier gives a retaliatory slap to Endicott was the first time on screen a black man had struck a white man. It's actually not true, with even Sidney's own history featuring earlier incidents; Band Of Angels, All The Young Men and The Defiant Ones just three examples out of many. Yet what really marks out this scene as so incendiary is that it's not set in the past, or two criminals fighting, or any of the other broader, less realistic situations that the actor had appeared in. This is a film made when the civil rights movement was still in full flow, and it was a present-day story set in the south, where the film was eventually banned. The scene, arguably the most pivotal in his entire career, almost acts as a powderkeg for what was going on in the real world.

A timeless, flawless film, and the winner of five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Rod Steiger. Although Poitier's own omission, not even nominated, is a point of contention, this is a film that succeeds on every level, from acting, to direction, to music, script and lighting. A sensational murder investigation set against a backdrop of intense racial politics, it's one of the few "race" movies Poitier did that feels every bit as relevant and powerful in the present day. As astonishing fifty years on, it's lost none of its power or authenticity, a true classic.